H. P. Lovecraft's The Temple: A Detailed Summary and Literary Analysis

- Michael Kellermeyer

- Mar 14

- 9 min read

Updated: Mar 15

Written in 1920, “The Temple” is as obvious a reworking of the themes in “Dagon” as it is a quaint predecessor of the grand visions of “The Call of Cthulhu.” All three stories explore the concept of an inscrutable, submarine civilization, and are themselves inscrutable in what they hint at, never fully pulling back the curtain. The most perplexing of these, however, is “The Temple.” Without the benefit of a framing device – like the many used in “Cthulhu” – it represents an incomplete story relayed by a single narrator who lacks the additional perspective needed to fill in the missing pieces. It would be as if Gustaf Johanson’s narrative of the Alert’s encounter with Cthulhu had been published without the added accounts of Thurston, Legrasse, and Angell.

As such, it feels incomplete and impressionistic, although that may be the effect that Lovecraft had intended. If so, the story – like Arthur Machen’s “The White People,” Ambrose Bierce’s “The Death of Halpin Frayser,” Henry James’ “The Turn of the Screw,” and Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” – is a delightful literary riddle, inviting its readers to consider the scanty evidence and imagine a solution.

II.

Stylistically, however, the story bears the most similarity to Poe’s work – most particularly his “MS. Found in a Bottle,” to which it is an unquestionably homage. Both stories feature men lost at sea in disabled vessels, a period of worry overcome by the euphoria of discovery (once the hope of rescued has faded into acceptance), an encounter with a strange, supernatural culture, vague revelations which gradually – though never wholly – piece together an understanding of what the narrator has discovered, and a puzzling conclusion in which the narrator seals and releases his story in a bottle before confronting his strange, underwater demise.

As such, interpreting Lovecraft’s confounding story may be easier if we keep in mind the main themes of Poe’s earlier work, namely, a stoic meditation on the inevitability of death, the euphoria of discovery for discovery’s own sake (rather than for mankind’s), the doom of civilization, the universal experience of mortality (we all go to the same place in the end), and the strange beauty of embracing death, living in the present, and experiencing the precious moments of life on one’s own terms despite the adverse catastrophes we may be handed.

These themes are also held in common with many of Poe’s other survivalist tales (“The Pit and the Pendulum,” “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” etc.), but Lovecraft gives it his own jaded flavor by making the narrator a repellent anti-hero, though one with whom – despite his attempts to make him cartoonishly villainous – our author clearly resonates.

SUMMARY

The story is framed as the final account of Karl Heinrich, Graf von Altberg-Ehrenstein, a proud and highly disciplined German U-boat commander. His manuscript, found by unknown means, describes a series of harrowing events that led to the loss of his submarine and crew. The tale begins with the destruction of a British merchant ship off the Iberian coast and the subsequent strange occurrences that plague the vessel.

The U-29 torpedoes an Allied vessel, leaving no survivors except for one body that drifts toward the submarine. This corpse is found clutching a small ivory carving of a strangely beautiful and otherworldly face. The German crew, initially dismissive, soon finds the relic disturbing, but von Altberg retains it for himself, captivated by its craftsmanship.

The presence of the dead body unsettles the crew, who report unnatural expressions on its face. The sailors become increasingly uneasy, claiming to hear whispering voices and see strange visions. Von Altberg, a strict and rational officer, dismisses their fears as hysteria, despite an atmosphere of growing dread.

As the submarine continues its patrol, crew members begin to suffer from hallucinations and night terrors. They claim to see ghostly figures and hear whispers in an unknown language. Some insist the dead sailor’s body, which was cast into the sea, continues to haunt them. The commander remains skeptical but notes the increasing paranoia among his men.

Panic overtakes the crew as several members mysteriously die or are driven to madness. Tensions reach a breaking point when a group attempts mutiny, blaming von Altberg for their fate. He quells the uprising with ruthless efficiency, executing dissenters and confining others. However, the deaths continue, and the crew’s numbers dwindle further.

The submarine begins to drift uncontrollably, seemingly drawn downward by an unknown force. The remaining crew, now reduced to only a few men, suffer worsening mental breakdowns. They claim that the ocean outside is alive with strange lights and figures, watching them from the deep.

Eventually, only von Altberg and his loyal lieutenant remain. The officer, once as rational as his commander, succumbs to madness, raving about an underwater city and its ancient inhabitants. In a final fit of hysteria, he throws himself out of the submarine’s hatch, vanishing into the dark waters below.

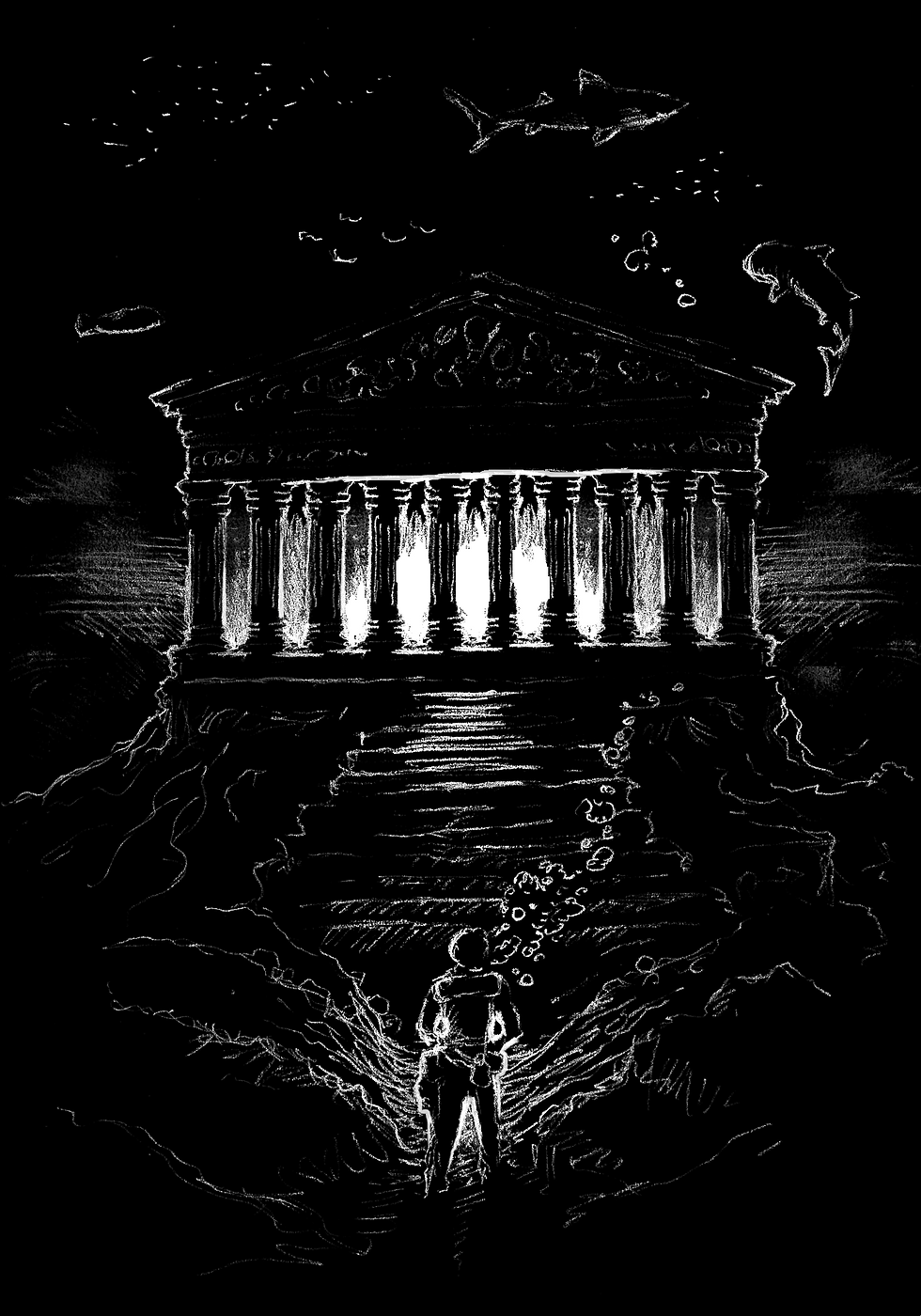

Now alone, von Altberg finally beholds the incredible sight outside his vessel. The submarine has settled upon the ruins of an ancient and impossibly vast underwater city, adorned with strange carvings and symbols. The architecture is unlike anything known to man, suggesting an advanced civilization that predates human history.

Mesmerized by the grandeur of the city, von Altberg feels an inexplicable pull toward a massive structure resembling a temple. He no longer considers escaping but instead becomes convinced that he is destined to explore this forgotten realm. His once rigid rationality crumbles as he accepts the supernatural reality before him.

Von Altberg realizes that the ivory carving he took from the dead sailor resembles the statues and reliefs inside the temple. He understands, too late, that the artifact was a harbinger of his fate. He no longer fears his doom but embraces it, believing he has been chosen to join the beings that dwell in the deep.

With no hope of returning to the surface, von Altberg prepares to leave the submarine and enter the temple. He writes his final words, acknowledging his inevitable transformation and expressing a strange reverence for the ancient civilization awaiting him. His fate remains ambiguous, but it is clear he willingly submits to whatever awaits beyond the threshold of the temple.

The story ends with the discovery of his manuscript, its exact means of reaching the surface unexplained. It serves as a cryptic warning, or perhaps an invitation, to those who might seek to uncover the mysteries of the deep. The tale leaves readers with an overwhelming sense of cosmic horror—an insignificance of humanity against forces beyond comprehension.

ANALYSIS

Before we continue into the analysis, a fair warning: Lovecraft did have a definitive solution to this story from which I will quote, and it may be less imaginative, creepy, or interesting than any theories that you may be mulling, so before you read on, you’re welcome to skip this analysis if you don’t wish to be disappointed. Before we get into that, however, let’s spend a moment considering the narrator whom Lovecraft chose to be mankind’s emissary to this subterranean missing link in our cosmic identity. I can’t help but note that Lovecraft’s famous racism is playing strange tricks in this particular Prussian persona.

On the one hand, it is a cartoonish (though no less racist) caricature of Prussian aristocrats that easily could have come out of Rocky and Bullwinkle, Dr. Strangelove, or Hogan’s Heroes – all of which would be more excusable because they are unapologetic comedies. His almost comic disinterest for human life, racism against anyone – including less “German” Germans (viz., everyone other than himself) – masturbatory musings on his “iron Jairmin vill,” his fetishization of German doctors and authorities, and his melodramatic pride in German “Kultur” all pile up into a fairly heavy-handed example of stereotyping.

S. T. Joshi opines that the tale is heavily “marred” by what he considers a “crude satire on the protagonist’s militarist and chauvinist sentiments.” And yet… as we spend more time with dear Von Altberg-Ehrenstein – or more to the point, as Lovecraft does – it becomes apparent that our author is rapidly warming up to his villainous Prussian. His disregard for life is truly pragmatic, his lack of mercy is almost philosophical, his impregnable skepticism is admirable, his racism against Alsatians and Rhinelanders is implied to be justified, and his lack of emotion, humanity, or concern for his own life is lauded as downright “Roman.”

Lovecraft sets us up to view him as a craven villain, but he turns the tables on us (or at least tries to): Von Altberg-Ehrenstein ends up – without ever questioning his heart or actions, or ever changing his opinions or values – becoming one of Lovecraft’s most lionized heroes. Unlike the weak-willed Yankee mariner in “Dagon,” this gallant Nietzschean meets his fate like a man, leaving us to wonder what point Lovecraft expects us to take away from this wily rascal: on the one hand, he seems detestable (mostly because he is a dirty, no-good Hun) and on the other, Lovecraft telegraphs the man’s genius, bravery, and sound philosophies.

This alone has not led to the story’s mixed reactions: Joshi – one of the most generous and biased of Lovecraft’s apologists – grumbled about its “excess of supernaturalism” and the “many bizarre occurrences that do not seem to unify into a coherent whole.” In Tour de Lovecraft, Kenneth Hite calls it “a fine little tale,” spending the vast majority of his tedious analysis comparing it to other entries in Lovecraft’s corpus (viz., how it acts as a keystone between “Dagon”-style stories and “Cthulhu”-style stories). His only direct commentary (and the closest thing to praise) is a supposition that it might be the first submarine-based horror story. And just in case you suspect that I’m giving Old Providence a bad rap, we are now ready to move onto Lovecraft’s explicit intentions for the story – in his own words.

II.

As I warned you earlier, Lovecraft was clearly aware that he had made a literary puzzle (and perhaps not a terribly good one). In a damage-control letter to Frank Belknap Long, he felt the need to clarify it’s meaning – before it was even published by Weird Tales:

“My submarine city is a work of man – a templated and glittering metropolis that once reared its copper domes and colonnades of chrysotile to glowing Atlantean suns. Fair Nordick bearded men dwelt in my city, and spoke a polish’d tongue akin to Greek; and the flame that the Graf von Altberg-Ehrenstein beheld was a witch-fire lit by spirits many millennia old.”

In short, far from being lured to his just deserts by the spirits of his drowned victims and murdered crewmates, Altberg-Ehrenstein is being guided to a “Nordick” Valhalla of honored rest among his Aryan ancestors. Indeed, dolphins have been traditionally interpreted as messengers from the sea gods who are sent to escort the souls of drowned sailors to paradise, making them the maritime version of Valkyries, and possibly suggesting that these obviously supernatural beings are perhaps not sabotaging him so much as guiding him to his rest among his equally misunderstood, equally vanquished ancestors.

Like Randolph Carter, Robert Olmstead, and Mr. Delapore, he is unable to find solace in a topsy-turvy world run by degenerate Alsatians and Rhinelanders, Jews and Catholics, Southern Europeans and African-Americans, immigrants and reformers. Far better to descend beneath the waves (just as Carter descends into subconscious sleep, Olmstead into submarine Y'ha-nthlei, and Delapore into his estate’s subterranean ruins) to join his place among the unappreciated relics of human civilization. If we do read it this way, it is yet another Lovecraft story arguing in favor of numbing out: seeking solace in the insular world of dreams and fantasies – and it is one with an arguably “happy” ending.

III.

Now, to be fair, there are unquestionable hints that something fishy is going on: there is the maniacal laughter in his mind, the faces of the dead gaping at him through the portholes, and the supernatural interference dating back to the appearance of the grisly, swarthy-skinned corpse from the Victory. If it weren’t for Lovecraft’s own written context, I would be inclined to believe that a very nasty surprise awaits his sociopathic submariner in the Temple. Most likely, I would have theorized that – as with The Wicker Man – he was summoned to be the sacrifice on its altar, and that the light from its windows comes from the sacrificial flames, rather than a “witch-fire lit by spirits.”

And perhaps – since Lovecraft rarely likes his narrators to experience a happy ending – this is what is meant to be implied, but the more we get to know the captain, the more Lovecraft seems to like him and make him seem likable. He is noble, realistic, brave, and Stoic, and his choices – other than gunning down the Victory’s lifeboats, which set off this misadventure – all seem to be logically correct (at least from a robot’s reasoning).

Far from a villain, after all, he is a visionary – a philosophically admirable Übermensch. Even his submarine, with its library, portholes, spotlight, and diving suits, is cribbed far more from the proto-Nietzschean Captain Nemo’s steampunk Nautilus than from the cramped, oily reality of a World War One U-boat. Truly (Lovecraft seems to indicate), this stoic intellectual was “too good” for this world, and his pathetic crew were unworthy of his time and attention.

Indeed, once he is disencumbered by his religious, working-class, culturally diverse crew, our atheistic, aristocratic, pure-bred Prussian boy-genius is finally able to pursue cosmic mysteries in pure, delicious isolation – which sounds an awful lot like a Lovecraft wish fulfillment. But then again, I can’t help but think about the altar in that temple and wonder what exactly did Altberg-Ehrenstein see when he passed through the doors, and who exactly was there to receive him. Perhaps – like a Soviet Chekist who has inevitably fallen out of favor, and finds himself being butchered in the same execution room he helped design – he did end up reassessing his cold-blooded worldview after all.

Every delivery counts in cricket, and Betongame knows it. That’s why Betongame Line Cricket gives users minute-by-minute betting options, making every over even more thrilling. With features like quick bet placement, constantly shifting odds, and full match coverage, fans can turn their passion into real-time predictions and rewards. Discover how the excitement of live cricket multiplies with Betongame: https://betongame.com/line/cricket

The BateryBet BD mobile app ensures that your betting experience is not confined to a desktop. Optimized for both Android and iOS devices, the app offers full functionality, including live betting, account management, and secure transactions. Its user-friendly design ensures that placing bets on the go is both easy and efficient. Download the app and enhance your betting experience by visiting click this

slot gacor slot gacor slot gacor slot gacor

your blog is really beautiful slot gacor