H. P. Lovecraft's The Doom that Came to Sarnath: A Detailed Summary and Literary Analysis

- Michael Kellermeyer

- Jul 25, 2024

- 11 min read

Expanding on the themes introduced in “Dagon,” and presaging the fleshed-out Deep Ones of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” “The Doom That Came to Sarnath” is arguably Lovecraft’s best effort in crafting a story in the style of Lord Dunsany. Indeed, critic Kenneth Hite – in his seminal commentary Tour de Lovecraft – struggles to restrain himself in gushing praise for the tale, calling it, among other things: “a terrific, terrific story,” “like caramel,” “one of [Lovecraft’s] three best pre-1926 tales,” “his perfect ‘Dunsany’ story,” “surprisingly mature,” and asserting that Lovecraft “writes nothing to touch it for two more years, although ‘Cats of Ulthar’ comes perhaps close.”

While I would shy away from discrediting such early tales as “Randolph Carter,” “The Outsider,” “The Picture in the House,” “The Nameless City,” and “The Terrible Old Man,” Hite is correct in his assessment that the story is his best reproduction of Dunsany. Specifically, he notes that Lovecraft is pastisching Dunsany’s “Time and the Gods,” and that Lovecraft’s contribution is writing a story which is more developed (perhaps even more padded and plodding), and which expresses its original mythology in a far darker voice.

Dunsany’s mythos has a Late Classical tone – similar to the finely-cadenced, orderly histories of Virgil and Ovid (pragmatic, aristocratic, and detached) – while Lovecraft’s “sound like early myth, something desperately smooshed together by Hesiod or hinted at by Euripides and translated by a shocked Cotton Mather.”

In short, Lovecraft’s historiography is dramatic with a tragic sensitivity to the roles of fate, hubris, and pathos in what he presents to be the cataclysmic downfall of a worthy civilization – one brought down not by its earlier cruelty (as most modern readers will naturally suppose), but by its lack of watchfulness and its inability to take history seriously.

SUMMARY

“There is in the land of Mnar a vast still lake that is fed by no stream, and out of which no stream flows. Ten thousand years ago there stood by its shore the mighty city of Sarnath, but Sarnath stands there no more.”

So opens our tale, which goes on to describe the circumstances which led to the collapse of a antediluvian civilization which would seem to be on par with the Babylonians, Persians, or Syrians in terms of scale, culture, and might. They began as a tribe of nomadic herdsmen who began to grow in influence as they gradually colonized the port towns along the River Ai until they had surged into a superpower. Surrounded by deserts, yet thirsty for more territory, they turned their attention to the sinister and silent lake where the Ai deposits its water. It was here that the colonists erected their capital – built from scratch – the citadel of Sarnath.

But even as Sarnath bloomed into a Shangri-La, Xanadu-style “pleasure dome” dripping with culture and decadence, there were tensions between the settlers and the locals – a strange tribe who inhabits the nearby city of Ib, where they worship the Great Water Lizard Bokrug. These beings are so bizarre in appearance that they were rumored to have descended from the moon:

“[they were] in hue as green as the lake and the mists that rise above it.... They had bulging eyes, pouting, flabby lips, and curious ears, and were without voices.”

Repulsive to look at, hear, or watch move, the people of Ib posed no immediate threat to the people of Sarnath (indeed, they were “weak, and soft as jelly to the touch of stones and arrows”), but – like the old man with the vulture eye in Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart” – their nonconformity became the subject of obsessive hate and prejudice on the part of the Sarnathians.

One night, overcome by their disgust, the men of Sarnath made ready for war, massacring the unarmed citizens of Ib, razing the city, and carting off the idol to Bokrug as a trophy, installing it in their own temple in homage to their gods. Before leaving, they pushed the corpses into the lake with their long spears (“because they did not wish to touch them”) along with all the rubble left over from their strange, monolithic, stone architecture.

The men of Sarnath now have full dominion over their land: there are no threats, no competitors, and no challengers: all fear the power of Sarnath. But before they have a chance to celebrate, something strange happens: the evening after the raid, “weird lights were seen over the lake,” the massive, stone idol of Bokrug disappears without a trace of evidence, and the chief priest of Sarnath is discovered dead on the floor, having written the hieroglyph for “DOOM” on the now-vacant altar in his final moments.

Many are disturbed by this, but most laugh it off and move on. Only the priests and old women keep the story in the back of their minds and are foolish enough to fear its implications.

A full millennia later, no doom has come to Sarnath: “the wonder of the world and the pride of all mankind was Sarnath the magnificent.” It continues to thrive as an unchecked metropolis of might -- 50 million strong -- although it has unquestionably become lazy, decedent, and eccentric in these later centuries.

Lovecraft describes its lush extravagancies and imaginative amenities in liberal detail, ranging from rudimentary air conditioning, scented fountains, ornate mosaics and murals, sophisticated botanical gardens, and amphitheaters so large that they could be flooded to reenact sea battles and allow gladiators to spar with captured sea monsters.

Now every year, on the anniversary of the massacre of Ib, the people of Sarnath threw a great celebration. It was at this time – and only at this time – that the waters of the lake tended to rise, as with a flood or tide, but a sea wall held them back (a wall, incidentally, which was the only defense on that side of Sarnath: it was completely unprotected by fortifications on its lakefront boundary, as if to taunt the sunken corpses of Ib).

For the 1000-year anniversary, a special shindig was planned, and ambassadors, nobles, and all manner of dignitaries from Sarnath’s neighboring allies flooded into the city to share the spectacle and remember the famous Sack of Ib.

The night begins well, with elaborate foods, including curiously large fish from the lake, and indulgent entertainment. But not everyone is comforted: the old women and the priests (who “liked not these festivals”) have still, centuries later, maintained their quiet fear of Ib, and as the revels crest at midnight, the priests (who nightly monitor the lake from a watchtower, as they have for a millennium) notice a green, misty vapor rises from the ugly water, heading for Sarnath. Soon after, repulsive shadows are seen descending from the moon, into the mist.

The party-goers are stunned and horrified to see the waters of the lake surging to engulf Sarnath, and all of the visiting dignitaries quietly packed and fled the city in instinctive terror. The calmness eventually descends into panic:

“Then, close to the hour of midnight, all the bronze gates of Sarnath burst open and emptied forth a frenzied throng ... so that all the visiting princes and travelers fled away in fright. For on the faces of this throng was writ a madness born of horror unendurable...

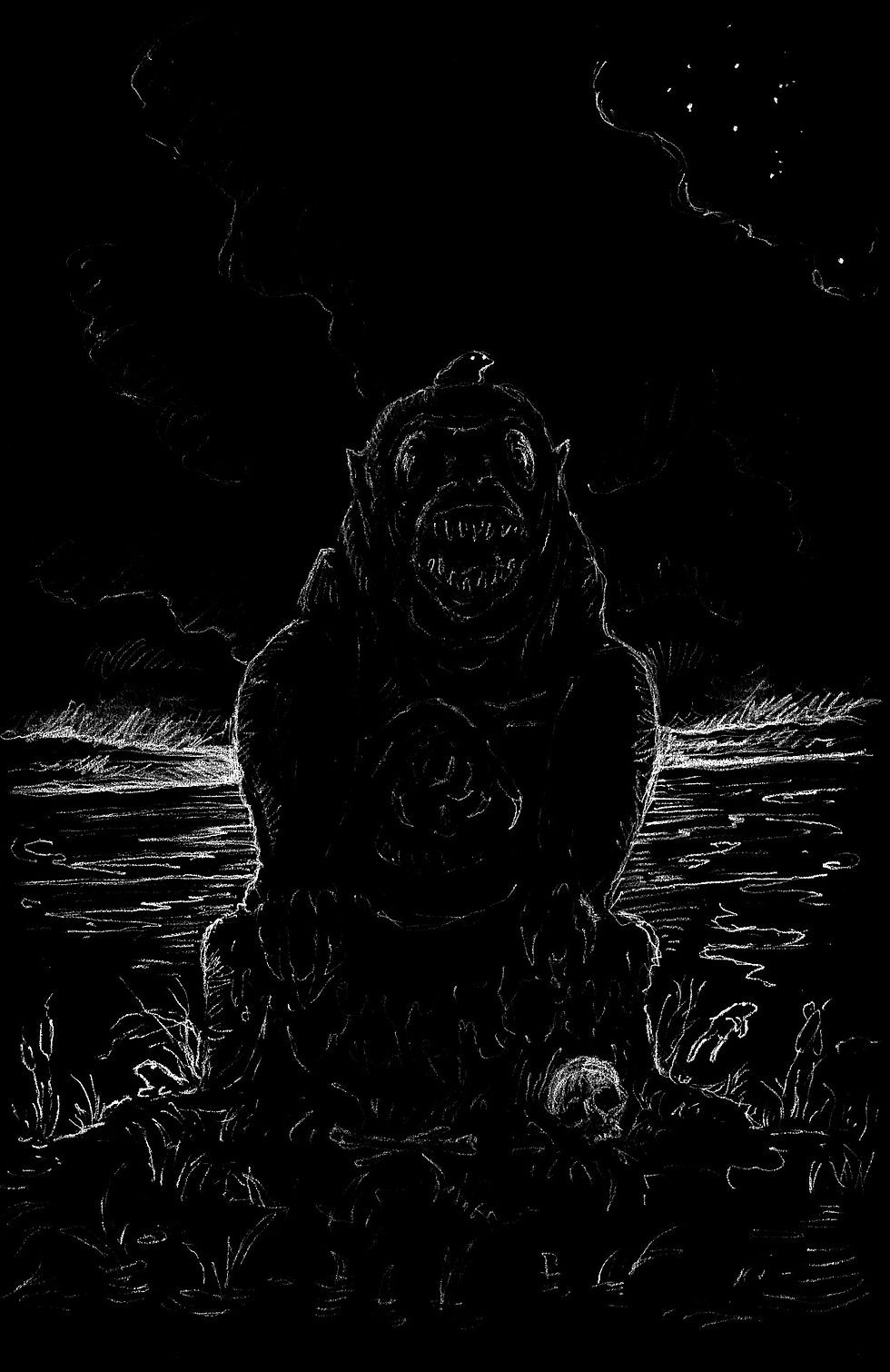

"Men whose eyes were wild with fear shrieked aloud of the sight within the king’s banquet-hall, where through the windows were seen ... a horde of indescribable green voiceless things with bulging eyes, pouting, flabby lips, and curious ears; things which danced horribly, bearing in their paws golden platters set with rubies and diamonds and containing uncouth flames.”

While the visitors are able to escape, it appears that the locals were massacred, but no one knows for sure: after the survivors return to their countries to tell the tale, the area around Sarnath is entirely avoided and uninspected for years.

Finally, some adventurous young men decide to investigate, but find the city completely vanished: although the lake is still there and the familiar landmarks, there is no sign of Sarnath, just “marshy shore, and where once had dwelt fifty million of men now crawled the detestable water-lizard.”

There is one, single relic left to signify that the wasted land around the lake had ever been visited by a civilization – the once-missing, green-stone idol of Bokrug the Great Water Lizard.

From that day forward, the detestable image of Bokrug was worshiped by all humans throughout the land of Mnar.

ANALYSIS

Modern readers will likely interpret this story – as they are entirely justified in so doing – as a sort of “I Spit on Your Grave”/”Last House on the Left”-style tale of cathartic revenge against a brutal oppressor. If this were history instead of literature, such an interpretation would be obvious and necessary. I have no doubt, however, that Lovecraft intended it to be a wholesale tragedy – more of a “Texas Chainsaw Massacre”/”The Hills Have Eyes”-style drama of degeneracy triumphing over a set of doomed, attractive heroes.

Aside from their obvious hubris (Lovecraft offers multiple examples of how the people of Sarnath slowly lowered their guard until only a few priests and old women held any fear for the creatures of Ib), the residents of Sarnath are depicted as being civilized, accomplished, and exceptional, having achieved feats in science, engineering, economics, and the arts which put them well ahead of any historical human civilization up until the Industrial Revolution. His gushing descriptions of their achievements and luxurious lifestyles – rendered without any significant detractions save from their lessening fear of Ib and their expanding imperialism – fails to color them as anything less than an admirable empire.

But like all kingdoms, this one has its date with fate: in a description that unquestionably borrows from the cataclysmic failures of the Babylonian, Roman, French, and Russian empires, Lovecraft has Sarnath overtaken by its enemies in the span of a single disastrous night. As mentioned in the introduction (and although I do understand feeling sympathy for the victims of Sarnath’s savage genocide), I think that Lovecraft’s ultimate message is less one appealing to multicultural tolerance than it is one lamenting the relaxing of watchfulness and the loosening of traditions. Sarnath, he seems to argue, fell prey to its own comfort and lack of vigilance rather than to its just deserts, and the squamous creatures of Ib are hardly intended to be pitied so much as feared.

II.

An anthropological reading of this story (one where the Beings of Ib are read as analogous to minority races, indigenous peoples, or immigrant populations) is a truly depressing thing to ponder, and although Lovecraft surely wouldn’t have had any problems with such a monstrous thing, I still believe that a more useful interpretation lurks beneath the obvious allegory of racism and imperialism. As with “Dagon,” I believe that the core concern and chief anxiety is less one of internal struggle between human factions and more of a worry of what degenerate impulses were bubbling up in the collective unconscious of humanity writ large: in short, that this – like “Dagon” – is a parable intended to describe humanity’s looming descent back into its animalistic, uncivilized roots.

To be fair, Lovecraft’s social solution to this would itself be arguably uncivilized (viz., a militaristic, authoritarian state rooted in flushing out crime and “degeneracy” through force – see: “At the Root”), but there is something unquestionably prescient and compelling (particularly in our age of social media, political division, mass killings, and deaths of despair) about the narrative that we are turning into something detestable and abhuman. The men of Sarnath repelled the Beings of Ib in order to create a space for human flourishing, in a very utilitarian sense: it was unfortunately accomplished through imperialism, slavery, and capitalism, but the end result truly was a city on a hill that embodied the loftiest ambitions of humanity.

Sarnath’s empire represented the apex of science, engineering, and the arts, attracting pilgrims and tourists from all the corners of the globe. It is an epicurean’s paradise, devoted to pleasure, aesthetics, indulgence, achievement, and learning. And at the end of the story, the people of Mnar no longer look up in awe at its walls and towers, but bow down in worship to Bokrug, the water-lizard.

III.

Once again, we may be wise not to interpret Bokrug – at least for a moment – as a harmless indigenous deity suppressed by Anglo-Saxon imperialists or Christian Nationalists, but as a truly repellent totem of evil. If so, then what does Bokrug represent? I would argue the descent into a purposeless existence – shapeless, aimless, and hopeless. Bokrug is a masturbatory god, one who symbolizes a circular existence without ambitions or aspirations, a gelatinous, pulpy deity like his worshipers who resists the urge to create and settles for an uninspired life of fruitless consumption.

I would also argue that it is an existence that Lovecraft himself feared he was personally experiencing: despite his famous arrogance and chauvinism, he was deeply insecure and ashamed of his family’s mental health, poverty, and even their looks. He feared that civilization as a whole, his family particularly, and he personally were on a death-spiral to madness, degeneracy, and shame, and it is worth considering that the Beings of Ib worshipping Bokrug at the beginning of “Sarnath” are not terribly different from the humans of Mnar doing the same at its end.

This may be a story – for all its obvious parallels to racism and imperialism – which is ultimately less about the Other among us and far more about the Other within us: our potential to be overtaken by our most miserable and m0nstrous impulses, to be dragged back down into the muck and mire of evolution, back into the primordial soup where we will provide no better contributions to our communities and civilizations than half-sleeping toads burping from their muddy nests.

IV.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t spend at least some time drawing attention to Lovecraft’s influences, from which he draws liberally, to the point of pastiche. The most obvious of these is Dunsany, specifically his “Idle Days on the Yann” (see our analysis of “The White Ship” for a summary) and the entirety of his Time and the Gods anthology (which was also a potent influence on Tolkien and Le Guin). Lovecraft borrowed Dunsany’s “olden time” manner of speaking, his exotic naming conventions, his elaborate alternate universe, his epic drama, his decadent epicureanism, and his supernatural mythos (viz., competitive, animalistic races, pantheistic gods, magic, priests, and wizards).

Next, Lovecraft borrowed from two specific biblical narratives. First is the tale, from 1 Samuel 5, of how the Ark of the Covenant was captured by the Philistines and brought into the Temple of Dagon where it was stored in front of Dagon’s idol. This came to no good, however, because the next morning the idol was first found toppled, and then – the following morning – it is discovered viciously smashed. Soon, plagues of rats and boils devastate every Philistine city where it is moved. Unnerved, the Philistines send the Ark back to Israel in the back of a driverless oxcart.

Secondly, there is the story of Belshazzar’s Feast from Daniel 5, where the eponymous Babylonian king holds a brazen orgy where he uses golden chalices and plateware stolen from the Jewish Temple for his guests. At the apex of the wild party, a phantasmic hand appears and scrawls a message of doom on the wall (hence the idiom: “the writing on the wall”) to indicate the imminent, catastrophic end of Belshazzar’s reign. Indeed, that very night the city of Babylon is invaded by the Persians and Belshazzar is assassinated during the chaos.

Finally, there is the unavoidable influence of Poe, who had a strong predilection for stories about debauched, aristocratic parties that are ruined by the specters of doom and decline. Most famous, of course, are “The Masque of the Red Death,” “The Haunted Palace,” and “Hog-Frog” (each of which also see a prince and his courtiers destroyed in a single night”), but don’t forget “The Shadow – A Parable,” “Metzengerstein,” “William Wilson,” and even “The Cask of Amontillado,” all of which feature the destruction of a dynasty at the culmination of some feast or festival.

Likewise, Sarnath is brought low in the afterglow of its crowning expression of victory over Ib, Bokrug, and all they represent – the Shadow-Side, the Id (cf. “Ib”), the subterranean soul. This can all be summed up in the Stoic observation of Ralphie Parker: “Life is like that. Sometimes, at the height of our revelries, when our joy is at its zenith, when all is most right with the world, the most unthinkable disasters descend upon us…”

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

google留痕 google留痕;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

온라인 슬롯 온라인 슬롯;

온라인카지노 온라인카지노;

바카라사이트 바카라사이트;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

google seo…

03topgame 03topgame;

gamesimes gamesimes;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS Machine…

EPS Machine…

seo seo;

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger…

seo优化 SEO优化;

bet bet;

google seo…

03topgame 03topgame;

gamesimes gamesimes;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS Machine…

EPS Machine…

seo seo;

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger…

seo优化 SEO优化;

bet bet;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

google 优化 seo技术+jingcheng-seo.com+秒收录;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群

gamesimes gamesimes;

03topgame 03topgame

EPS Machine EPS Cutting…

EPS Machine EPS and…

EPP Machine EPP Shape…

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

EPS Machine EPS and…

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Keep up with the latest IT security trends and learn best practices for the year ahead. From patch management to incident response planning, discover effective strategies to defend against cyber threats. Equip your organization with the knowledge and tools necessary to protect systems, data, and networks in an increasingly complex cybersecurity landscape.