H. P. Lovecraft's Agonizingly Lonesome, Subterranean, Gothic Fiction

- Michael Kellermeyer

- Sep 12, 2024

- 37 min read

Excerpted from our anthology The Outsider, The Rats in the Walls, and More Tales of Ghouls, Gods, and Graveyards: The Subterranean Weird Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft

“All my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large ... To achieve the essence of real externality, whether of time or space or dimension, one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all.

“…when we cross the line to the boundless and hideous unknown—the shadow-haunted Outside—we must remember to leave our humanity and terrestrialism at the threshold.”

— H. P. Lovecraft

THE LONESOME DEATH OF HOWARD LOVECRAFT

As he lay, sweating and cramped, tangled in the bedsheets of a hospital berth, Howard Philips Lovecraft was almost certainly piqued – with morbid irony – at the parallels between his fate and that of his lifelong idol, Edgar Allan Poe. Both men were laid low in their forties by a sudden, painful illness, hounded by financial instability, an abbreviated, controversial marriage, and mixed success in their literary work (which, even when successful, seemed overshadowed by a disappointing cycle of failure and loneliness).

At forty-six, however, Howard was a far greater flameout than his model: Poe was internationally regarded, professionally esteemed, and a man of the world who had made his way in life independently[1]. He had studied at West Point, held down many prestigious jobs, kept house in four major American cities, cultivated a loving (if impotent) marriage, stirred up constant, attention-grabbing rivalries and scandals, and earned the admiration of respectable, middle-class readers before his mysterious death at forty. All in all, he was misunderstood, controversial, and tragic – but his effectiveness as a poet, journalist, and critic was the least debated element of his dynamic life, and his death left a notable hole in the nascent community of American literati[2].

By comparison, Howard was a high school dropout, had never been conventionally employed, lived in the same city for almost his entire life (save for a miserable, two-year stint as an unemployed house-husband), was divorced after two years of awkward cohabitation, and was too obscure to make any significant artistic waves during his lifetime.[3] Finally – while he succeeded in attracting a loyal cadre of young admirers – they were mostly outsiders just like him: underemployed, bored, single, struggling daydreamers working clerical jobs, living with their families, and finding their only delight in pulp fiction rags peddling sword-and-sorcery escapism. His life’s work was admired only by this fringe subset of subscribers to magazines like Weird Tales, Argosy, Home Brew, and Amazing Stories, but was never noticed by literary academics, professional writers, or establishment critics during his lifetime.

His agonizing demise was consistent with his famously nihilistic philosophy, one which rejected humanism as a foolish vanity, spirituality as wishful thinking, and even science as ill-advised meddling. This is sharply expressed in the iconic opening lines of “The Call of Cthulhu”:

“We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far… [lest we] open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

Discussing this particular passage John Gray[4] asserts that it serves as a thesis statement for the author’s hallmark cosmicism, which he summarizes as holding that:

“The human mind is an accident in the universe, which is indifferent to the welfare of the species. We can have no view of the scheme of things or our place in it, because there may be no such scheme. The final result of scientific inquiry could well be that the universe is a lawless chaos. Sometimes called ‘weird realism,’ it is a disturbing vision with which Lovecraft would struggle throughout his life.”

In short, we might say that Lovecraft’s message is that life has no heroes, no hope, and no Hollywood endings. This was certainly the way things were looking for him as he chronicled his daily activities and increasing pain in what would come to be called his “Death Diary” as intestinal cancer consumed his body[5].

Perhaps, in spite of all his carefully marshaled pessimism, he had allowed himself to hope for a happy ending – for recognition and esteem in his community – but as the paragraphs in his diary shortened into clinical sentences, then into staccato words (“pain” being the foremost refrain), it was clear that there might have been something to his Stoic nihilism after all.

The writings of his philosophical hero, Friedrich Nietzsche, may have come to mind – mad, lonely Nietzsche, who had become a celebrity among disaffected young men at the turn of the century by declaring the death of God, the irrelevance of good and evil, and the right of might; Nietzsche, who bitterly decried the slave morality of the weak masses which he saw to be foisted upon the backs of their superiors (the Übermenschen) – an odious worldview of feminine subservience which, he held, stifled their pseudo-divine Will to Power[6]. If so, the Master’s famous quip, “the meaninglessness of suffering, not suffering itself, was the curse that lay over mankind so far” would have been an apt meditation during Lovecraft’s misery.

His diary ceased four days before his death, the pain being too immense for concentration. Before losing his senses to the agony, he may have pondered these unfavorable parallels with Poe, but there was no question as to which man had been more successful at his craft: Poe’s death stunned his readers and the American literary order; Lovecraft’s would sadden his plucky network of teen fanboys, amateur horror writers, and penny-pinching pulp editors, but his legacy seemed doomed to die with him, fading into oblivion once his few dozen followers had moved onto other pursuits and forgotten him[7].

In just two or three years he would likely be just another footnote in genre fiction – another forgotten amateur like Paul Annixter, George W. Crane, Mrs. Harry Pugh Smith, or Ferdinand Berthoud[8]. As Gray notes (with clinical simplicity equal to his subject) he died in a state of resolved hopelessness “convinced that his work—which had received only slight recognition in his lifetime—would soon be forgotten entirely.”

LOVECRAFT UNDER REVIEW:

HIS WORK, HIS INFLUENCE, AND HIS LEGACY

This was not, however, the end for H. P. Lovecraft: in some sense, he did end up with a Hollywood ending – as a heroic underdog whose legacy is resurrected and preserved by the young admirers whom he had selflessly served in life. Indeed: at odds with the harsh, Social Darwinist worldview that he espoused, Lovecraft had written many hundreds of encouraging letters to his young fans (aspiring writers and editors themselves) who esteemed him as a venerable father figure, and – as they grew up and came into prominence as professional authors – they loyally took up his cause, ensuring that his work would remain in print[9]. Frank Belknap Long, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, and August Derleth were among the most famous Lovecraftian disciples who devoted themselves to preserving and expanding upon his Cthulhu Mythos.

Ironically, it was the patient compassion he showed these alienated teenagers – answering their questions, forwarding them books, critiquing their writing, and encouraging their dreams – that secured his fame as a writer whose horror stressed the insignificance of all life and the purposelessness of living[10]. Two years after his death, August Derleth founded Arkham House as a platform to keep Lovecraft on bookshelves, releasing two massive omnibuses – The Outsider and Beyond the Wall of Sleep – during the World War II years, before publishing anthologies of classic supernatural fiction by the likes of J. Sheridan Le Fanu, William Hope Hodgson, H. Russell Wakefield, and original novels and anthologies in the same milieu by Smith, Long, Bloch, Derleth, and their own new wave of young, literary disciples (e.g., Ray Bradburry, Charles L. Grant, Ramsey Campbell, and Brian Lumley)[11]. By the late 1960s, Lovecraft’s distinctively proto-postmodern, deconstructionist cynicism was warmly welcomed by anti-establishment youth, who included him in a place of honor alongside Joseph Heller, Hermann Hesse, and J. D. Salinger on their mantels[12].

With the ascent of the fantasy and horror-influenced Heavy Metal and Prog Rock subcultures, Lovecraft’s story titles began to show up as tracks on albums by Black Sabbath, Caravan, The Fall, Blue Öyster Cult, and (of course) the psychedelic band H. P. Lovecraft[13]. In 1981 the roleplaying game Call of Cthulhu was released by Chaosium, and from that point on – while Lovecraft would require another twenty years before he could be truly considered mainstream – his legacy would be devoutly guarded and passed on by successive generations of young outsiders, one to the other[14].

“Today,” as Michael Dirda observes in his article “Cthulhu for President,” “Lovecraft is rightly regarded as second only to Edgar Allan Poe in the annals of American supernatural literature… In fact, Lovecraft has moved from cult writer to cultural icon.”

Google’s Ngram feature demonstrates how each generation discovers Lovecraft, almost anew, surging him to a new peak in popularity before he would inevitably decline in their interest (presumably as they pass out of moody adolescence, begin to experience success and belonging in the world, and become invested in the human project that Lovecraft disdained)[15].

And yet – almost like clockwork – just as the reigning generation seems to hand their Lovecraft collections into the thrift store, the rising generation restores his name with force. The Silent Generation peaks with Lovecraft in 1949 before apparently outgrowing him in 1958. The Baby Boomer Generation almost immediately seems to recover his legacy, causing him to surge in popularity throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s (with noticeable spikes in ’62, ’68, ’73, ’78, ’80, and – a precipitous spur in 1983 – in the wake of Call of Cthulhu).

Gen X was – surprisingly – less enthusiastic, with Lovecraft’s popularity cratering in 1991, before experiencing an anemic recovery to 1983 levels (it isn’t exactly a “peak,” though) in 2003. Here, however – as s0-called “nerd culture” came of age and found mainstream acceptance in the custody of the Millennial Generation, Lovecraft’s popularity skyrocketed – almost exponentially – doubling interest in ten years[16].

In 2015, however, in the aftermath of the Michael Brown killing, the Charleston mass shooting, and Donald Trump’s golden escalator speech, Lovecraft’s compounding popularity notably shudders to a halt. By the other side of Trump’s 2016 presidential victory, he began to slip sharply in popularity, and – as of the writing of this in April 2024 – he has lost twelve years of gains with Millennials and Gen-Zers, slipping just below his 2012 numbers.

The message has been clear: Lovecraft spoke deeply to young people – particularly Baby Boomers and Millennials – but there has been a vocal rejection of his legacy in the past decade, one which may be temporary or – as with many controversial, public figures in the 2010s – decidedly permanent[17].

One of the questions that I hope to pose in this introduction and the following commentary is why – aside from his inexcusable racism – Lovecraft’s trademark, misanthropic, cosmic philosophy has exceeded its shelf-life, and whether there is any value left of his art which can be salvaged. This criticism is particularly salient during our post-postmodern age when humanism’s social justice ethos and environmentalism’s Anthropocene pathos[18] have simultaneously been sanctified as universal, mainstream orthodoxies.

In such a socio-political climate – one equally secular and self-righteous – the Cthulhu Mythos’ spiritual purposelessness is not remotely as frightening as the existential doom of climate change[19] or as intellectually compelling as solving corporate corruption. In short, the 21st century has proven far too moral to forgive Lovecraft’s insensitivity to human dignity, and far too material to be either awed or scandalized by his suggestion that humans are animals without souls or intrinsic meaning. So, what is left? I would argue there is still much, and a great deal of it can be mined from his earlier, Subterranean Cycle.

THE SUBTERRANEAN H. P. LOVECRAFT:

DEFINING THE BOUNDARIES OF HIS GOTHIC ERA

Lovecraft’s work – by his own estimation[20] and by that of his scholars – fell into three distinct categories: there were his Poe tales (which emphasized psychology, degeneracy, and the Gothic), his Dunsany tales (which emphasized fantasy, decadence, and the poetic), and his Lovecraft tales (which – influenced by Arthur Machen, Robert W. Chambers, and Algernon Blackwood – emphasized misanthropy, nihilism, and the cosmic). Of course, as any reader of Lovecraft will observe, these trends, though observable, were nebulous and complimentary throughout his life, regularly building upon and calling back to one another (cf. 1917’s “Dagon,” 1928’s “The Call of Cthulhu,” and 1936’s “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”). As Jose Luis Arroyo-Barrigüete notes[21]:

“most critics … suggest that his literary production can be grouped into three different periods: the Macabre (1905–1920), the Dream Cycle (1920–1927) and the Cthulhu Mythos (1925–1935). Having said that, it is impossible to categorize the stories by their dates of creation, as they overlap, while containing elements that thematically fit a different cycle. The Dream Cycle and the Cthulhu Mythos share many aspects and themes, blurring the line between the categories further.”

Nevertheless, Lovecraft’s legacy has primarily hinged on the later of the three stages, which generated his most original and memorable pieces: “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Dunwich Horror,” “The Colour Out of Space,” “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” “At the Mountains of Madness,” “The Haunter in the Dark,” and “The Shadow Out of Time,” among others. These later tales – written after the deaths of most of his loved ones, the failure of his marriage, his humiliating retreat from New York City, and the loss of the adventuring spirit which electrified his imagination as a child – are heavy with curmudgeonly nihilism.

Heartfelt emotion, close friendships, and hope for humanity (elements which, though rare, made occasional appearances in his early work) are purged from his writing, leaving the clinically unsentimental voice that resonates so deeply with his fanbase (especially young, angry, disenfranchised males) who feel so alien to society that they glory in his Nietzschean apathy.

Certainly, the later “Lovecraft Era” stories are masterworks, brimming with imagination and action; they will never cease to occupy a place of honor among the canons of science fiction, horror, and fantasy (or the genre, so inextricably associated with him, which blurs all three equally: weird fiction). “The Call of Cthulhu” will never stop being an exciting read. “At the Mountains of Madness” will never fail to awe. “The Whisperer in the Darkness” will never misfire its sheer creepiness. These stories – so reverently favored by Lovecraftian scholars – will never be overshadowed by his less visionary, more derivative early works when it comes to imagination, cosmicism, or cinematic scope.

For the purposes of this anthology, however, we will be focusing on what we call Lovecraft’s Gothic Era: the period leading up to the landmark years of 1926 and 1927, which saw him pen his first great extraterrestrial masterpieces (“The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Colour Out of Space”) along with the respective apotheoses of his Poe and Dunsany eras (the Poe-esque “Case of Charles Dexter Ward” and Dunsanian “Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath”).

The following year, 1928, would demonstrate a firm shift in tone and scope, with the Machen-influenced “Dunwich Horror,” succeeded by a slew of science-fiction novelettes haunted by Chambers-inspired extraterrestrials: “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” “At the Mountains of Madness,” “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” “The Shadow Out of Time,” and “The Haunter of the Dark.” Interspersed between these were a handful of Gothic-tinted throwbacks to the old days: “The Dreams in the Witch House” (a Hawthorne/Machen homage), “The Thing on the Doorstep” (a Chambers pastiche), and “The Evil Clergyman” (a nod to Bram Stoker).

1926 was the year when Lovecraft fled New York for Providence, allowing his marriage (along with any hopes for an independent, “normal” life away from the influence of his family) to fizzle, surrendering himself to what he must have viewed as the inevitable fate of little Howie Lovecraft: to stagnate, shrivel, and die in the narrow confines of his limited, lonesome childhood[22].

In short, 1926 was the year that Lovecraft accepted the pathetic fate that awaited so many of his protagonists (sheltered, submissive loners desperate for friendship and adventure): a life of insecurity, obscurity, and dejection. This failure led to a massive transition in Lovecraft’s themes, vision, and voice, which caused him to abandon his introspective, Poe-inspired writing in favor of the more clinical, misanthropic science-fiction which shifted the locus of danger from the bowels of the earth and the caverns of individual human hearts to the darkling stars gazing hatefully overhead at the entire human race.

No longer was his attention on the degeneracy or inherited vices lurking within human souls – he had relocated it to a hypothetical, existential threat from the universe without. Interior conflict was traded for cosmic drama – and to good effect: I will never deny the power and scope of the great, later stories beginning with “The Call of the Cthulhu’s” non-Euclidean metropolis and terminating with “The Haunter in the Dark’s” three-lobbed eye. These expansive, imaginative nightmare-scapes fuel thought and provoke awe. But something powerful was lost in 1926 when Lovecraft stepped off the train to Providence.

In his final deeply Gothic story, “Pickman’s Model” (written alongside “The Call of Cthulhu” late that summer), there is a strange sense of transition and passing-on: the eponymous artist disappears into the secret world of ghouls, but unlike Harley Warren (“Statement of Randolph Carter”) or St. John (“The Hound”), he is allowed to simply fade away into that good night without suffering a savage demise (a fate confirmed in “The Dream-Quest” where he reappears as a joyfully acclimated, fully transitioned ghoul).

It is almost as though Lovecraft was permitting himself – and his now-dated Gothic sensibility – to pass on peacefully into obscurity (not unlike the ghoul-befriended protagonist of the similarly-themed “Outsider”), descending one last time into the subterranean regions into which he had so feared being absorbed, before shifting his focus from the raw and intimate channels of the human heart to the cold and distant, cosmic vistas of “The Whisperer in the Darkness” and “At the Mountains of Madness.”

THE GOTHIC TRADITION AND

THE SUBTERRANEAN H. P. LOVECRAFT:

DECAY, REPRESSION, AND ISOLATION

When referring to “the Gothic” most readers will have a general sense of what is meant: it is evocative of spooky-castle aesthetics, supernatural perils, eccentric decadence, stormy nights, and shocking secrets. It suggests sinister, lonely places whose fabulous ruin symbolizes some equally degenerate heart: one imagines the works of Poe or Hoffmann, Universal Studios monster movies, the Brontë sisters’ novels, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Tim Burton, Vincent Price, and Alfred Hitchcock. But what the Gothic actually means – beneath the obvious aesthetic trappings – is less widely understood.

By definition, Gothic fiction concerns itself with the looming threat of physical, spiritual, and social decay. In American Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion, Cristoph Grunenberg associates the Gothic with a “fascination with death, horror and the macabre,” drawing on Shamim Momin’s definition of Gothic sensibility as one which “revels in a voluptuous, sensual materiality. Decay and fragmentation, ruin and dissolution describe both the specific forms as well as their allegory of moral, corporeal, emotional, or socio-political [concerns].” Critic Paul Margau notes that (as with so many of Lovecraft’s early stories):

“one of the major characteristics of Gothic literature is that it has a ripple effect, over time and space, on our concepts of Self and Society, due to its being a distinct type of literature, with a function of psychological release, mediating the conflicts and sociocultural anxieties of the writer and of the reader[23].”

Renata R. M. Wasserman describes it as

“a genre agreed to be particularly appropriate for the expression of cultural, as well as psychological anxieties of a subterranean kind, hard to acknowledge in other ways[24]” [emphasis mine].

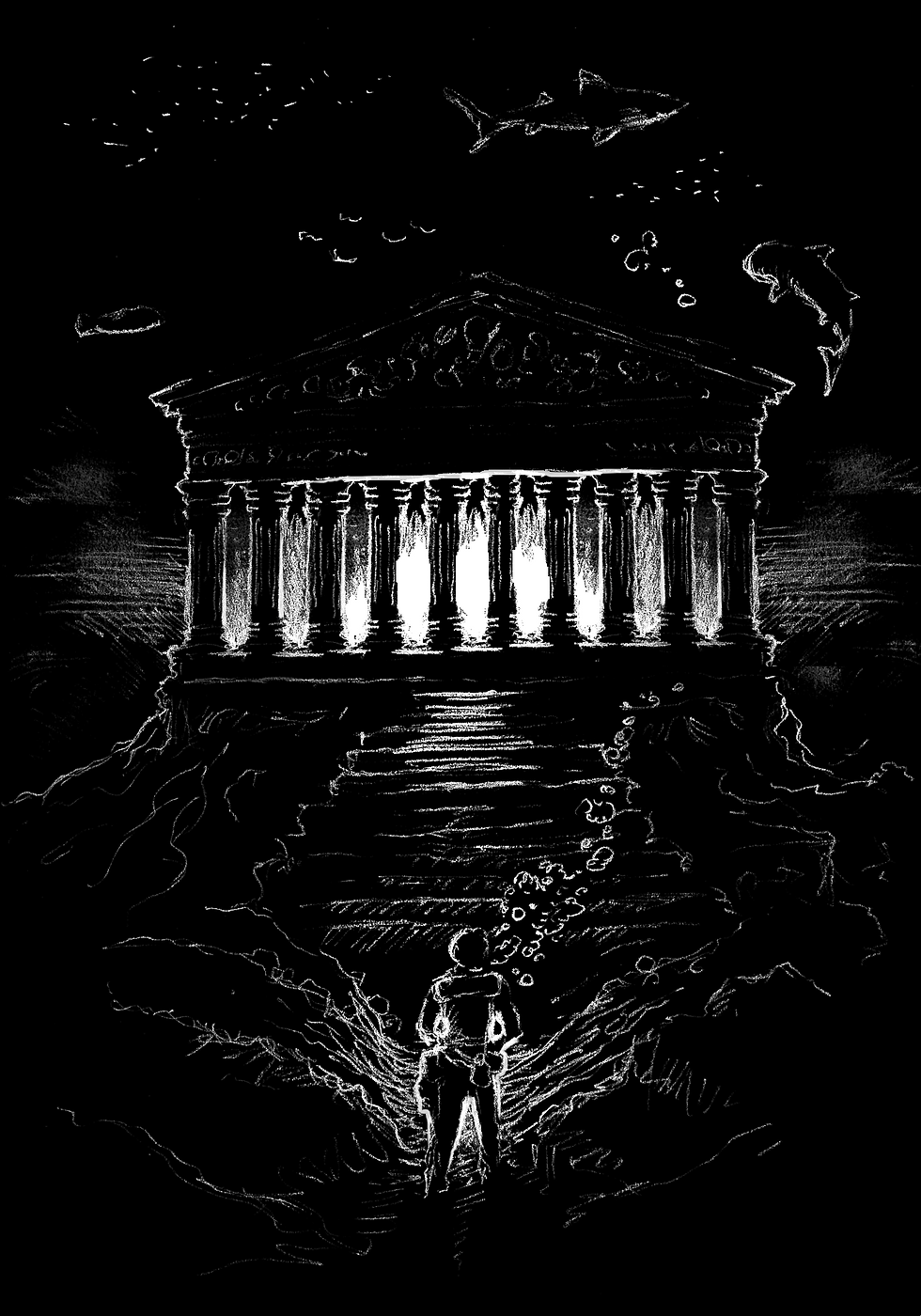

Her use of the word “subterranean” is, of course, particularly apt when considering the concentration of the Gothic ethos in the first half of Lovecraft’s career – a period which significantly focuses on sepulchral settings, burrowing monsters, and underground perils. It is for this reason that the present anthology correlates “The Subterranean H. P. Lovecraft” with “His Gothic Era.”

So what was Lovecraft’s Gothic Era? Borrowing Arroyo-Barrigüete’s timeline for reference, we would argue that this stage in Lovecraft’s writing subsumes his “Macabre Tales” and “Dream Cycle” phases, lasting from youth until the publication of “The Call of Cthulhu,” following his disappointing return from New York City in 1926. For the first decade of his professional career,[25] Lovecraft’s writing heavily emphasized interior angst, heavily borrowed Gothic tropes from Dark Romantics, Decadents, and Edwardian supernaturalists[26], and was mostly concerned with the specter of moral, psychological, and spiritual degeneration (either individually as a protagonist or collectively as a civilization).

They involved tales of forbidden knowledge, hereditary curses, vengeful spirits, decadent villains, haunted houses, psychopathic hermits, evil forces, encounters with otherworldly dimensions, the dormant dead, and terrible old men brooding like hungry spiders in dangerously lonely places.

Above all, they typically involve some exploration of an underground or cloistered setting, or an incursion from the denizens of such a hidden space – spaces which are, of course, symbolic of the human personality: secretive, private areas where monsters are able to breed without threat or detection.

A full third of these stories literally involve cemeteries, tombs, or burial places of some stripe, ranging from the graverobbers in “The Statement of Randolph Carter,” “Herbert West – Reanimator,” “The Nameless City,” and “The Hound” to the macabre mishaps in “The Tomb,” “The Outsider,” “Under the Pyramids,” and “In the Vault.” Another subset of tales concerns that beloved Gothic symbol of internal degeneration, the haunted house, which features in tales as obvious as “The Shunned House,” “The Lurking Fear,” “The Alchemist,” and “The Rats in the Walls,” to subtler uses of the trope which focus on haunted men hiding away in nasty hermitages far from human eyes, morality, and reason (“Erich Zann,” “The Cats of Ulthar,” “The Terrible Old Man,” “The Picture in the House,” and “Pickman’s Model”).

A third subtype of tales ponders sunken or buried ruins that have been lost to time and history (e.g., “The Temple,” “Polaris,” “The Moon-Bog,” “The Doom that Came to Sarnath,” “Dagon,” “The Festival,” and “The Nameless City” [again]). Even the more ethereal among these (which can also be included in the fantasy-heavy, Dunsanian Dream Cycle) – “Polaris,” “Nyarlathotep,” “The White Ship,” “What the Moon Brings,” and “The Horror at Martin’s Beach” – each concern a shocking confrontation with a buried reality, one which aggressively resurrects (challenging the protagonist’s understanding of reality) before leaving them alone in utter alienation.

These first four stories also involve forgotten ruins of dead civilizations and psychedelic dreams of death (are they dreams, though?) which torment their isolated protagonists with the specter of Oblivion, while “Martin’s Beach” follows the formula of “Sarnath” by having an unexpected revenge executed against mankind through the sudden surfacing of a secreted, underwater terror (cf., “The Temple,” “The Cats of Ulthar,” and “Dagon”).

Each of these stories involves a horrible, hidden thing that is regrettably discovered in some lonesome place – either in a cave, cemetery, crumbling castle, hermit’s hovel, or narcotic nightmare – bringing shame and despair on the protagonist, who is shaken in his faith in humanity. It is no wonder that – steeped as they are in Gothic archetypes – subterranean themes would permeate them. As Alex Bevan remarks in Gothic Literary Travel and Tourism:

“In addition to the multitude of religious, mythological, philosophical and folkloric subterranean narratives that have developed over the course of history, there are an abundance of Gothic texts that are fuelled by the explorations of underground space. The inception of the Gothic mode with ‘The Castle of Otranto’ (1764) by Horace Walpole inscribed the subterranean dungeon as a marker of Gothic sensibility. Dungeons are fraught spaces of locked desire and symbolise the various models of entrapment endured by the characters in Gothic fiction. The underground becomes a metaphor for the unearthing of buried histories, ancestries and secrets in Gothic narratives.”

He goes on to note, quite helpfully:

“Subterranean Gothic spaces are explored most explicitly in the works of H. P. Lovecraft. Many of Lovecraft’s tales feature monstrous, subterranean realms that are on the cusp of surfacing into the everyday… In [“Pickman’s Model”] the well [in Pickman’s basement] functions as a form of vacuum releasing subterranean demonic energy from the underworld to the surface, demonstrating the ways in which historical, religious discourses feed into subterranean Gothic texts. James Kneale argues that ‘Lovecraft’s fiction is explicitly concerned with thresholds, with metaphors of contact and transgression.’ The ‘thresholds’ identified by Kneale are often subterranean, unearthing savage monsters, threatening the civilized world above.”

Like the masters who came before him – Poe in particular – Lovecraft utilized cloistered and underground spaces to illustrate the violent forces of human repression and the way in which they channel their compressed energy into moral degeneration. Consider the anxious outbursts of Madeline Usher bursting from her crypt, Montresor burying Fortunato alive in his own catacombs, or the “Tell-Tale Heart” narrator’s battle with his conscience as he straddles the floorboards under which his victim is entombed.

Furthermore, look at the repressed rage of attic-bound Bertha Rochester (Jane Eyre), the moldering Mrs. Havisham (Great Expectations), or the delirious convalescent writing from her confinement in “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

Now, to be sure, his writing comes nowhere near the complex interiority of Poe, Brontë, Dickens, or Perkins-Gilman (not to mention the three S’s (Shelley, Stoker, and Stevenson), who also wrote capably about psychological torment, moral dissonance, and repression in the context of hidden settings and secret misdeeds), but his work, while less overtly profound, is still powerfully concerned with the internal workings of his isolated, longing protagonists.

Although Gothic themes would permeate every single horror story that he ever wrote, the Gothic sensibility was strongest in these early tales from his first decade of professional writing, tales which were (often infamously though frequently effectively) indulgent imitations of the 19th-century Gothic masters.

From its very inception during the 1760s, Gothic literature has occupied itself with exploring alienation and otherness. At times this has been executed against otherness (cf. the seductive, foreign aristocrat, Count Dracula; the sociopathic, Decadent dandy, Dorian Gray), while in many instances it was expressed from the perspective of otherness (cf. Frankenstein’s Creature; the Phantom of the Opera; Beauty and the Beast), typically exploring the complex spirituality and psychology of the Outsider. While the Gothic works of Poe, like those of Lovecraft, typically lack this (often feminine) knack for humanizing monsters, they nevertheless centered themselves squarely on the perspective of disconnected loners longing for acceptance and peace.

Such was the case in most of Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, which often follow the frustrated longings of an isolated intellectual, who is gradually consumed by his disordered passions. This is particularly true of “Metzengerstein,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “Ligeia,” “Morella,” “William Wilson,” and “Berenice,” among others.

“The House of Usher,” in particular (it would serve as the model for many of Lovecraft’s best Gothic tales[27]) tells the story of a neurotic eccentric whose pathological sensitivity is so acute that he has become a hermit holed up in his crumbling, ancestral manor with his dying twin sister. When the sister – whose health is compromised by centuries of inbreeding – finally appears to die, her brother has her buried in the family crypt, full-well knowing (by way of his keen hearing) that she is actually alive.

Trying to survive apart from her (she can be said to represent material life and he can be said to represent intellectual life, which are housed together in the House, which represents the human body), he grows gradually more insane until his sister breaks out of her crypt (symbolizing the futility of denying mortality), confronting her brother with her reality by throwing her bleeding body on top of his: an act which kills them both, resulting in the spontaneous demolition of the physical House of Usher which – bereft of intellectual and material life – crumbles around them in utter Death.

ALIENATION BEFORE THE ALIENS:

LOVECRAFT AND THE MISBIRTHED HORROR OF HUMAN LONELINESS

It should not be surprising that a story like this (and the many by Poe which resemble it) would prove inspiring to Lovecraft. His childhood had already been severely blighted by trauma, beginning with his father’s institutionalization, and the death of his grandmother, which shuttled his family into what he termed a profound “gloom from which it never fully recovered[28].”

This was followed by the loss of his grandfather’s fortune (which led to the dismissal of the family servants – yes, Lovecraft actually did grow up with servants), the public shame of his family’s fall from prominence, his grandfather’s death from a stroke (brought on by shame and anxiety from his business catastrophes), and the subsequent loss of the family estate. It was at this point that young Howard ceased writing, overwhelmed – at the age of eighteen – with suicidal thoughts, and shoved to the brink of a mental collapse by the stress and uncertainty of his family’s situation.

As the only surviving male, he should have been able, so he thought, to provide for his mother and aunts – the “man of the house” – but his ambitions and hopes were swallowed up in insecurity and instability. Before he could even graduate high school, he was overwhelmed by a “sort of a breakdown” which he describes as a “general nervous weakness which prevent[ed] my continuous application to any thing[29].”

His plans to apply to Brown University were dashed, and the well-read, patrician-tongued Lovecraft would die without ever attending another day of classes – an unemployed high school dropout living with his impoverished family, too overwhelmed with his own insecurities and pride to find work to support his equally unindustrious kinswomen.

The next five years have precious little documentation: we only know that his family fell more deeply into poverty, that further business failures hounded his uncle, that he avoided leaving the house, except at night, because he was “so hideous that he hid from everyone and did not like to walk upon the streets where people could gaze on him,” and that he and his mother would recite passages of Shakespeare tragedies so violently that the next-door neighbors mistook them for domestic screaming matches (or at least that’s what Lovecraft claimed the neighbors were overhearing: his mother was certainly not a kind or gentle woman, and their relationship was notoriously stressful)[30].

During this period, he tried to study chemistry and astronomy but was overwhelmed with the necessary mathematics, and in his frustration, turned to writing aggressively racist poems with such uplifting titles as “New-England Fallen” and “On the Creation of Niggers,” including a piece of white supremacist sci-fi called “Providence in 2000 AD” which depicts a new millennium where Anglo-Saxon Protestants have been overtaken by hordes of nasty Jews and Catholics.

He was severely unwell.

He turned to reading amateur pulp magazines and was elevated to cult status in this niche realm because of his vicious letters to the editor, which roasted the style of one of the leading contributors, whose work he considered “effeminate,” “coarse,” and “proper to negroes and anthropoid apes[31].” Burning with pent-up aggression, searing misanthropy, and an aimless intellect thirsty to spar, Lovecraft began writing reams of letters to the editor, goaded by his rabid fanbase (early 20th century “shitposting”).

It was in this frame of mind, teetering between the darkest years of his life – hounded by family ruin, personal shame, and the shadow of suicide – and his meteoric rise in the commentariat of pulp periodicals that he penned his first adult story, “The Tomb,” which follows a lonely boy who is drawn to a crypt in the woods near his house where he begins spending his time among the bones of 18th-century decadents, who once lived in a manor which was destroyed by lightning while the family was inside partying.

These forays increase in intensity and imagination, and as he grows up, they take on a necrophiliac nature, mounting up to a hallucinogenic trance that reveals him to be the reincarnated spirit of the most depraved member of the family. After reexperiencing the manor’s Usher-like destruction, he is found wallowing amongst the bones and is summarily institutionalized.

This story followed what would eventually become a proven formula for his Gothic stories: A wandering loner finally finds a connection with an unusual or forbidden source --> He goes too far in his exploration of this feeling of belonging --> As a result of his hubris, he is ejected from this communion in a dramatic climax --> …which leaves him eternally alone.

This is far different from the formulae of his later, “Lovecraft Era” stories, which are much less interested in the psychology of loneliness and belonging (themes which had become, perhaps, too painful to ponder by his forties), transitioning to macrocosmic themes which involve a collective doom for the whole of humanity rather than the social struggles of a solitary character. While nothing can steal the celestial power from these mature works, these earlier Gothic tales probe sensitive areas of the human experience which are rarely, though unfairly, associated with their author.

REANIMATING LOVECRAFT FOR A HUMANIST FUTURE:

DECONSTRUCTING HIS DEFANGED

NIHILISM AND MISANTHROPY

But there is a serious and growing problem for Lovecraft’s legacy – one which is becoming increasingly apparent as the years march on and Lovecraft’s Ngram score continues to slip at the same exponential rate at which it began to rise in the early aughts – though it isn’t perhaps the most obvious concern that we might first suspect.

Lovecraft’s repellent racism is so indissolubly tangled up in his personality, writing, and biography that – although it was the ignition source behind his explosive decline during the advent of the millennial-driven, intersectional Black Lives Matter movement[32] – if it were going to cause his exclusion from the literary canon, it would have happened long before. Indeed, Lovecraft’s particularly expressive brand of racism – one emboldened by his religious adherence to extreme Nietzscheanism and the terrifying science of eugenicists[33] – was so far outside the bounds of polite society in his own day, that it shocked his friends and family.

In the most famous example, his close friend, Samuel Loveman (the model for Harley in “The Statement of Randolph Carter,” and a proud, gay Jew) disowned his one-time friend, burned their correspondence, and lambasted him as a provincial vulgarian[34]. No, Lovecraft’s racism – revolting as it is – is not the primary threat to his legacy. That honor goes to the nearly universal success of his materialist, misanthropic worldview among the literary public and the academy.

Indeed, nihilism is more in vogue than ever before, with alarming results for mental health (globally, and for young people in particular)[35]. It is probably just as ubiquitous today as a de facto worldview as cultural Christianity was in New England during Lovecraft’s lifetime. A disproportionate percentage of serious literary scholars, readers, or critics agree – tacitly or explicitly – with the core message of Lovecraftian horror: humanity is a scientific mishap, our global doom is imminent, our existential purpose – if we must have one – is a cozy fiction relative to each individual, and we are ultimately scheduled for a summary extinction which will make a mockery of millennia of human self-mythologizing[36]. In short, life is meaningless and humanity is a cosmic joke at best and a planetary virus as worst.

Now, many intelligent people happen to take issue with most of these nihilistic claims[37], but – if I may speak anecdotally – nearly all of my own professors in grad school and most of my colleagues in a variety of English departments would check each one off with Stoic confidence. I would wager that most of the scholars who have dedicated their lives to literary criticism are in the same club: to them, human beings are odious, dangerous animals without a spiritual identity, destiny, or purpose. The thing is, however, most folks who keep this worldview aren’t at all horrified by this: wistful, perhaps, but they wear their misanthropic materialism like a badge of honor, and many scholars have turned the idea on its head, claiming that a meaningless existence is morally liberating – not frightening or dispiriting at all[38].

Originally, Lovecraft was morally shocking: the suggestion that we were without meaning or mission was dreadful. The implication that Earth – far from the gleaming, blue jewel invested with divine favor – was a swampy cesspit overcrowded by mutants and hybrids, destined to become a dead cinder, was uncomfortable at best and inconceivable at worst. The idea that human beings could devolve back into abhuman swine or cannibalistic apes, was repulsive to polite readership[39] (even though Darwin’s theories – and their social and moral implications – had been largely accepted as fact by the educated and upper classes – and especially capitalists captains of industry – decades before Lovecraft’s birth[40]). And the readers who agreed with Lovecraft surely felt elated to belong to such a select band of in-the-know Stoic magi.

No one else in their ratty little towns would have be capable of retaining their sanity if they realized the Truth™, but they could share this dark secret with dear Mr. Lovecraft, chuckling with pity at the delusional masses who wasted their time trying to repress their animal impulses, contribute to the public welfare, and provide for their families when nothing at all mattered (of course, the Lovecraftians still largely held down jobs, paid taxes, and didn’t make murder and ravishing a past-time, but not because they believed in fairy tales, human dignity, or universal moral truth).

The great blow, however, came during the 2010s when a curious thing happened to the postmodern materialists: their ranks were inundated by masses of new allies who – above all things – devoutly believed in universal moral truths[41]. Millennials with graduate-level educations began bringing their passion for social justice to societies that – while urgently dedicated to the libertarian ethos of “live and let live” – had little philosophical interest in defending causes from positions of moral certainty. University departments, corporate boards, and fandom conventions were suddenly pressured to take decisive stances on divisive social issues – something which hadn’t happened since the idealistic days of the 1960s, just before moral relativism became the fashionable philosophy of the Cold War West[42].

Within a single decade, two adjustments had been made in the most influential literary centers (from English departments and fan conventions to book chatrooms and literary conferences): firstly, the average literati accepted Lovecraft’s misanthropic thesis (humans are dangerous animals destined for self-inflicted extinction and ultimate ignominy), but secondly – and most importantly – they rejected his Social Darwinist morality (might makes right) in favor of warm-hearted humanism vigorously dedicated to propagating social justice and resisting oppression from a position of moral certainty[43]. What is an eco-centric, humanist skeptic supposed to do with H. P. Lovecraft? His existential terrors hold no horror for them (they are obvious and unsurprising) and his Nietzschean solutions are revolting and regressive.

But as most mature Lovecraft Legionaries will argue, there is more to his work than the miserable caricature of the bitter loner spewing racism from his aunt’s basement between meals of cold beans. There is something deeply emotional about his vision of the world – the raw pain of disappointed idealism. His heartbreaking Dream Cycle is often (literally) tear-inducing. His Gothic tales, which so often involve a lonely man finding (and then traumatically losing) his first and only friend in the world, are genuinely vulnerable. His descriptions of isolated boys coming to the humiliating realization that they are too repellant to rub elbows with the normies (cf. “The Tomb,” “The Alchemist,” “The Outsider,” “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”) are crushing to read.

While many will continue to adore Lovecraft for the awe-inspiring sublimity of his cosmic misanthropy, the purpose of this collection is – at least in part – to explore a much less studied element of his early writing: his raw humanity.

REGARDING THIS COLLECTION:

A WORD ON OUR SELECTIONS,

CRITICAL LENS, AND EDITORIAL VOICE

I will own that the editorial vision of this anthology – of its commentary and analyses – is deliberately reactionary. My intention is to frame it, at least in part, as a response against the last half-century of Lovecraft criticism, which has always been comfortable with Lovecraft’s misanthropy and moral cynicism. While I won’t waste any time joining the united chorus of critics heralding Lovecraft’s political chastisements, I do wish to deconstruct his nihilistic vision for humanity.

Various renditions of this contrarian philosophy were once delightfully embraced by libertarians, New Atheists, and counterculture sects during the second half of the 20th century, but they are all significantly less relevant in an age when mankind’s existential purposelessness is widely accepted and the social problems of the 21st century make moral nihilism – once the antagonistic, avant-garde creed of edgy uncles, The Dude, and Tyler Durden – painfully old-fashioned and impotent. As a result, some of my commentary will trend confrontational as I dissemble some of the long-cherished fundamentals of Lovecraft scholarship.

Chief among these gate-keepers, of course, is Sunand Tryambak Joshi, the godfather of Lovecraft studies and the assumptive expert (at least according to Penguin Classics and Hippocampus Press) on any writer of classic horror and weird fiction[44], from Robert W. Chambers to M. R. James (despite only nursing a fawning expertise in Lovecraft – the sole writer in the genre whom he appears to enjoy). While Joshi’s criticism is truly indispensable, and his insights are often profound, his monopoly in the field and his delusions of objectivity have allowed significant blind spots and dogmatic orthodoxies to develop in Lovecraftiana – sloppy missteps that do their greatest disservice to Lovecraft himself.

Other critics from the same generation (viz., Kenneth Hite, Peter Cannon, Robert M. Price – Baby Boomers all) share Joshi’s almost religious zeal for Lovecraft’s moral vision and anthropology (which best manifested in his later, post-1927 science fiction) without ever pausing to unpack the latent humanism and spirituality of Lovecraft’s writing (present throughout, but best manifested in his earlier, pre-1927 Gothic fiction).

By taking Lovecraft at his word and celebrating what should be considered an unwholesome and unhelpful moral prescription for a humanity that is still struggling to rise from the mire of in-humanity, these septuagenarian iconoclasts have missed the raw emotion of a disappointed idealist. Their lionization of Lovecraft as a consummate, contrarian bad-ass (whose Nietzschean Stoicism was just “too real” to let him be fall for the weak worldviews of bleeding hearts and bourgeois morality) has caused them to miss what stands out to less cynical minds who read between the lines of his stories and letters: the screaming pain of wounded idealism and disappointed hope. They miss the deep, humanity of Lovecraft’s broken heart.

SOUNDING THE BURIED HEART:

FROM SPITEFUL MISANTHROPY

TO FRUSTRATED DESIRE

Lovecraft longed for belonging and purpose, but since it was denied him almost from birth, he calcified his heart against all hopes, culminating in the dissolution of his marriage and his return to Providence (his living grave) where he accepted his fate. From this point, he transitioned from stories of inner conflict – stories which debated, skeptically, whether transcendence was even possible – to tales which promoted a now-forgone conclusion: the human project is a doomed failure, and our aspirations are a waste of time. So, he speculated, who or what “out there” would have the agency and purpose that humans so clearly lack? In these later stories, Cthulhu, the Mi-Go, and the Yog-Sothoths are not just threatening monsters: they are satisfying wish-fulfillments.

Ugly and odious though they may be, amoral and heartless though they are, they have a divine mission from the Great Old Ones, and their lives are rich with adventure, meaning, and victories over their lesser underlings. Lovecraft does not wish us to fear them – not really – he wishes us to envy them. Clinical, rational, and inhuman (perhaps not entirely unlike a certain amateur writer), they are able to pursue colonization of less evolved species, unhindered by the Slave Morality of lesser minds.

In his stories, these pathetic creatures are human beings writ large, but in his own life – perhaps, just perhaps – Lovecraft may have been imagining how glorious it would be to rise up out of his subterranean obscurity, alone and forgotten, to punish his own undeserving curs: progressive liberals, sincere religious people, hopeful minorities, enterprising immigrants, social reformers, close-knit families, and any other type of person who is moved by their ideals to sacrifice comfort for an aspirational “greater good.”

In the previously-alluded-to article by John Gray – “H.P. Lovecraft Invented a Horrific World to Escape a Nihilistic Universe” – the author makes the compelling case that Lovecraft’s pessimism stemmed from frustrated idealism, not smug superiority, and that his universe of terrors was a respite from the disappointment of his adopted worldview. Far from the black-pilled bad boy lauded by Gen-Z incels and Boomer New Atheists as a defiant paragon of unsentimental materialism, Gray paints a picture of a complex, lonely man lost between two vying systems of thought, neither of which he could claim: spirituality on one pole and scientism on the other.

While skeptics and rationalists claim Lovecraft as one of their own, the truth is that he was just as disgusted by their optimistic faith in science and human evolution as an opposite and equal extreme to the beliefs of Buddhists, astrologers, and Catholics. As Gray remarks:

“Throughout his adult life Lovecraft was an unwavering atheist and materialist. In a letter of 1918, he declared: ‘... the Judaeo-Christian mythology is NOT TRUE.’ At the same time he had nothing but scorn for the rival mythology of his day, the belief that humankind—'the miserable denizens of a wretched little flyspeck on the back door of a microscopic universe,’ as he described the species in the same letter—was at the forefront of cosmic evolution. For him the cosmos was a trap, and human beings the prey of blindly mechanical forces. His ‘Cthulhu Mythos’—a fictional alternate reality containing godlike minds far more powerful than those of human beings, and also utterly different from theirs—was a response to this vision.”

This “vision,” then – of Dread Cthulhu, the Black Pharaoh Nyarlathotep, and the incursions of savage Mi-Go – is the worshipful wish-fulfillment of a man preaching nihilism, but still desperately yearning for… something. Even a Great Old One who could take pity on him and enlist him (like Castro in “Call of Cthulhu”) as a cog in its pathetic cult of depraved, human traitors.

Lovecraft’s Gothic Era regularly followed weaker, younger, submissive men giving themselves over to stronger, older, dominant men (viz. Nietzschean Übermenschen) in pursuit of the stronger mate’s intellectual projects. Its Jungian symbolism suggested an internal battle between the unconscious Will to Power and conscious insecurities – a process of personal development that Jung called individuation.

After his withdrawal to Providence, his artistic interests shifted from such internal dynamics into a Dionysian, religious mythology. Materialist though he was, Lovecraft’s later tales were wish-fulfillments whereby his characters are noticed and dominated by the divine, cosmic actors. These stories may sound like science fiction written by a savvy materialist, but their seminal message is as old as The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Iliad: a fantasy (no matter how fearsome) of a reality where we look up to the stars and something (no matter how terrifying) sees us and looks back.

The rhetoric of Lovecraftian gods succeeds in arguing the pointlessness of the human project because they provide a “daemonical” counterpoint to the traditional worldviews of the major moral philosophies. The Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism can’t be worth pursuing if there is a Cthulhu. Feminist, Confucian, and Jewish social ethics can’t be valuable if Nyarlathotep reigns. Christian charity, forgiveness, and sacrificial love aren’t worth pursuing if the Great Old Ones are coming back. But what if (as Lovecraft assures us), his fantastical monstrosities are not real? That certainty fades away: the religious zeal with which he promoted his nihilistic worldview becomes just another forgettable tract in the mailbox, alongside the Jehovah’s Witnesses’, Hari Krishnas’, and White Supremacists.

The paradox of Lovecraft’s chosen genre (viz. supernatural fantasy), I believe, is that for him and his followers, the existence of eldritch monstrosities would be a dream come true: it would nullify what they believed to be the wasteful efforts that human beings have spent on metaphysics, social programs, and any number of self-denying moral disciplines (from the Peace Corps to Greenpeace and from Brahmins to Franciscans) would be categorically proven pointless. Indeed, the Great Old Ones almost appear to have been designed with fable-like care and craft – pedagogical archetypes intended to present lessons from a specific system of belief. It is, ironically, just one more series of myths designed to promote a worldview built on faith – faith in nothingness.

As Gray observes, “The paradox of Lovecraft’s writing is that although he believed myth existed in order to shield the human mind from reality, his own mythos seems to do the opposite: the ‘Outside’ is more frightening than the world in which human beings live.” With no gods or guiding principles in their unguided, godless world to preach their nihilistic gospel of relativism, Lovecraftians’ philosophy carries just as much weight – by their own moral standards – as the philosophies of Zoroastrians, social democrats, fascists, Mormons, feminists, or the Ancient Egyptians. Without Cthulhu – or any other deus ex machina – Lovecraft’s religion is no more likely than any other and his life, ironically, is propelled by a faith just as blind as any other.

It is a religion founded on a hope: in peaceful oblivion, that failures will be allowed to be forgotten, and shortcomings excused – a desire born from an entirely different series of hopes – hopes of transcendence, belonging, and purpose – which were systematically dashed throughout Lovecraft’s early life.

Poignantly, Gray concludes his essay:

“Lovecraft’s anti-mythology of slimy, inhuman creatures reflected an unresolved struggle within himself. He firmly rejected religious mythologies that accorded humankind a special place in the scheme of things, but he could not accept the implication of his materialism, which is that human life has no cosmic value or meaning. Rejecting any belief in meaning beyond the human world, he also rejected the meanings human beings make for themselves. He had no interest in the lives of most people, and from his early years seems to have believed his own would count for very little. He was left without any sense of significance. So, obeying an all-too-human impulse, he fashioned a make-believe realm of dark forces as a shelter from the deadly light of universal indifference.”

Today Lovecraft is lauded for his commitment to reality, for his giga-Chad disdain for sentiment and conformity, and for his aversion to mankind’s delusions of grandeur. But it may be that he, like us, was just another disillusioned Pretender, seeking consolation from fairy tales (of his own making) and hoping that the peace he found in them would stay by his side until the bitter end.

In his early, Gothic fiction, we certainly see these kinds of characters: young men who are desperate to belong, who open their hearts to domineering father figures in hopes of being protected, who gobble up the supernatural with faithful relish, and who earnestly, hopelessly yearn for social restoration and spiritual transcendence.

These Gothic tales repeat the story of lonely seekers pursuing metaphysical freedom, and being dashed down, like Icarus, to wallow in shameful disappointment. They expressed the wishes of his own telltale heart, which he would finally symbolically bury, once and for all, in “Pickman’s Model.” His desire to belong and thrive can be heard, weakly throbbing, in their protagonists’ longings, failures, and despairs, and they speak far more to the human experience than many of his more famous stories of cephalopodic invaders. And it is fitting, because – as much as he resented his species and as dearly as he wanted to divorce himself from all sentiment and emotion – Lovecraft was just as human and broken as any of us, and his early writing, especially, testifies to this.

Today he is an icon of confident non-conformity, but during his lifetime he was insecure, uncertain, and frustrated. He once had high hopes for restoring his family’s status and for gaining acceptance into the fickle halls of power, but time and reality chipped away at those desires until only a dedicated circle of fanboys remained to tether him to life.

***

Meanwhile, in Providence in the winter of 1937, Lovecraft is losing everything. Yes, he has admiring correspondents, and, yes, he has made a name for himself in the niche world of amateur weird fiction, but he is now inescapably confronted with the fact that his lifelong pretense at being a “superior man” – a fallen aristocrat whose breeding alone demands respect – has been one long false hope: a delusion just as subjective and intellectually dishonest as the faithful idealism he so despises in political activists, devout believers, and dreamers of all stripes.

His final years had been haunted by this gradual realization, a humiliation that pushed him further towards the dispassionate cynicism of “The Haunter in the Dark,” “The Thing on the Doorstep,” and other bleak portraits of hopelessness and forfeited agency. On March 15, incapable of writing any further words in his Death Diary, ravaged by pain and hounded by the humiliating ironies of his life, Howard Philips Lovecraft followed his master, Poe, into the mysterious oblivion he had so longed for.

This demise, however, should not be looked at with schadenfreude: it is an utterly human experience to fail, to lose faith in yourself, and to watch your dreams fade into disappointment. Despite all his undeniable unsavoriness, at heart Lovecraft died believing himself to be the ultimate Outsider – unacceptable, unlovable, unforgivable – and that tragedy should move us. It is for his broken humanity rather than his bitter misanthropy that I hope Lovecraft is remembered.

[1] Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy, Jeffrey Meyers

[2] His obituary in the New York Tribune – written anonymously by his bitter rival, Rufus Griswold – admitted that, with his death, “literary art lost one of its most brilliant, but erratic stars”

[3] I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft, by S. T. Joshi; Lovecraft: A Biography, by L. Sprague de Charles; H. P. Lovecraft, by Peter Canon

[4] In his convincing essay, “H. P. Lovecraft Invented a Horrific World to Escape from a Nihilistic Universe” – more on that later

[5] Death Of A Gentleman: The Last Days Of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, by R. Alain Everts

[6] Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography, by Rüdiger Safranski

[7] A Dreamer and a Visionary: H. P. Lovecraft in His Time, by S. T. Joshi; H. P. Lovecraft, by Peter Canon

[8] These long-forgotten, unstudied authors were all published alongside Lovecraft in the January 1924 edition of Weird Tales

[9] “Sixty Years of Arkham House,” by Kris Larson (Rain Taxi)

[10] “Letters to Robert Bloch and Others by H.P. Lovecraft,” a review by Darrell Schweitzer (The New York Review of Science Fiction)

[11] “Sixty Years of Arkham House,” by Kris Larson (Rain Taxi)

[12] The Strange Sound of Cthulhu: Music Inspired by the Writings of H. P. Lovecraft, by Gary Hill

[13] H.P. Lovecraft in Popular Culture: The Works and Their Adaptations in Film, Television, Comics, Music and Games, by Don G. Smith

[14] “Terror Eternal: The enduring popularity of H.P. Lovecraft,” by Stefan Dziemianowicz (Publishers Weekly)

[15] https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=H.+P.+Lovecraft&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=3

[16] H.P. Lovecraft in Popular Culture: The Works and Their Adaptations in Film, Television, Comics, Music and Games, by Don G. Smith

[17] “Pro and Con: Cancel Culture,” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

[18] Put simply: humanity is indelibly ruining the world and ushering in an unavoidable holocaust of all known life as a result of pollution, climate change, and material excess

[19] “Impending Doom: Youth Face Anxiety as The Planet Warms,” by Abby Wilt (Pepperdine University Graphic)

[20] “There are my 'Poe' pieces and my 'Dunsany pieces' —but alas— where are any Lovecraft pieces?” (from a 1929 letter)

[21] “Sentiment analysis of Lovecraft's fiction writings,” (Heliyon)

[22] “Marriage, Failure, And Exile: H.P. Lovecraft In New York,” by David J. Godwin (Gotham Center)

[23] “Changes of Perception in Gothic Literature,” (British and American Studies)

[24] “Gothic Roots: Brockden Brown’s Wieland, American Identity, and American Literature.” Ilha do Desterro

[25] Which started in 1916 with the publication of “The Alchemist,” written in 1908 while he was in high school

[26] Viz., Shelley, Hoffmann, Poe, Hawthorne, Stoker, Stevenson, Machen, Wilde, Henry James, Hodgson, Chambers, Blackwood, the Benson Brothers, and M. R. James

[27] Ex. “The Shunned House,” “The Tomb,” “The Outsider,” “The Alchemist,” “The Picture in the House,” “The Lurking Fear,” “The Rats in the Walls,” “The Music of Erich Zann,” “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward,” etc., etc.

[28] I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft, by S. T. Joshi; Lovecraft: A Biography, by L. Sprague de Charles; H. P. Lovecraft, by Peter Canon

[29] Ibid

[30] Ibid

[31] Ibid

[32] “We Can’t Ignore H. P. Lovecraft’s White Supremacy,” a 2017 article for Literary Hub by Wes House

[33] “Lovecraft and Nietzsche at the Mountains of Madness,” by Noam Tiran and Adam Etzion (Academia.org)

[34] “Of Gold and Sawdust” by Samuel Loveman

[35] “An Increase in Nihilism Plays Havoc With Mental Health,” by Charles Harper Webb, PhD (Psychology Today), “Growing Nihilism Among Young People,” by Istvan Orban (New Acropolis Library), “Generation Doomer: How Nihilism on Social Media is Creating a New Generation of Extremists,” by Daniel Siegel (Global Network on Extremism and Technology), and “‘New nihilism’: How Gen Z is embracing a life of futility and meaninglessness,” by Wendy Syfret (Sydney Herald)

[36] Sociology of Religion, by Neil Gross and Solon Simmons; A Philosophical Defense of Misanthropy, by Toby Svoboda

[37] “Misguided Misanthropy: Why the “Humans are the Virus” Mindset is Damaging to the Environmental Movement,” by Connor Farnham (Bard Center for Environmental Studies); Man’s Search for Meaning, by Viktor Frankl

[38] “Philosophy in a Meaningless Life: A System of Nihilism, Consciousness and Reality,” by James Tartaglia

[39] “The Dynamics of Xenogenetics and Sectarianism in Lovecraftian Horror: A Study of Nihilism and Sceintific Upheaval,” by Brandon L. Matsalia (CSUSB ScholarWorks)

[40] “Social Darwinism in the Gilded Age” (Khan Academy)

[41] “The Lost Promise of Reconciliation: New Left vs. Old Left,” by Armand L. Mauss (Journal of Social Issues)

[42] “Gen Z: How young people are changing activism,” by Megan Carnegie (BBC)

[43] “It’s Too Late to Redeem HP Lovecraft, Who Was An Unapologetic Racist and Anti-Semite,” by Crystal Contreras (Willamette Week)

[44] The Evolution of the Weird Tale by S. T. Joshi, a review by Neal Monks (SFCrowsnest)

Join the best Python training in Pune to master programming skills from industry experts. Gain hands-on experience with real-world projects, covering core concepts, advanced techniques, and popular frameworks. Ideal for beginners and professionals, the course offers flexible schedules, practical learning, and certification to kickstart your career in software development or data science.

Ethical Hacking Training Institute in Pune is a premier destination for learning cybersecurity and ethical hacking. The institute offers comprehensive training programs designed to equip students with the skills needed to identify and mitigate security vulnerabilities. With a curriculum with hands-on practice and real-world scenarios, students gain practical experience in network security, penetration testing, and cyber defense strategies.

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

google留痕 google留痕;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

온라인 슬롯 온라인 슬롯;

온라인카지노 온라인카지노;

바카라사이트 바카라사이트;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

https://www.gevezeyeri.com/

https://askyeriniz.blogspot.com/

https://soh--bet.blogspot.com/

https://yetiskinchatt.blogspot.com/

https://livechattt.blogspot.com/

Gabile Sohbet Cinsel Sohbet Yetişkin Sohbet

https://www.grepmed.com/chat1

https://divisionmidway.org/jobs/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://www.guiafacillagos.com.br/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://utahsyardsale.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

http://jobboard.piasd.org/author/yetiskinsohbet/

http://www.annunciogratis.net/author/yetiskinsohbet

https://employbahamians.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://rnmanagers.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://rnstaffers.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://www.i-hire.ca/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://veterinarypracticetransition.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://www.lotusforsale.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://aboutnurseassistantjobs.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://www.sitiosecuador.com/author/yetiskinchat/

https://aboutsnfjobs.com/author/yetiskinchat/

https://www.ocjobs.com/employers/3420821-yetiskinsohbet

https://jobs.theeducatorsroom.com/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://cuchichi.es/author/yetiskinsohbet/

https://www.ziparticle.com/author/yetiskinchat/

https://praca.uxlabs.pl/author/yetiskinchat/

https://rnopportunities.com/author/gabilechat/

https://rnstaffers.com/author/yetiskinchat/

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/gabilechat/

https://www.allmyusjobs.com/author/gabilechat/

https://www.nursingportal.ca/author/cinselsohbett/

https://www.fmconsulting.net/gymsforsale/author/gabilechat/

https://www.animaljobsdirect.com/employers/3424370-yetiskinsohbet

google seo…

03topgame 03topgame;

gamesimes gamesimes;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS Machine…

EPS Machine…

seo seo;

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger…

seo优化 SEO优化;

bet bet;