Edith Nesbit's The House of Silence (A Detailed Summary and Literary Analysis)

- Michael Kellermeyer

- Mar 15

- 12 min read

Updated: Mar 20

An elegant, poetic, and unnerving haunted-house-story, “The House of Silence” evokes the best works of Lord Dunsany, Edgar Allan Poe, and W. W. Jacobs with its emphasis on atmosphere and Nesbit’s muscular self-discipline. As such, it remains one of the most beautifully written of Nesbit’s entire oeuvre, an impressionistic prose poem percolating with suggestion and mood.

Indeed, I would argue that – along with “The Shadow,” “The Violet Car,” and “In the Dark” – “The House of Silence” is a shamefully underappreciated masterpiece. It may be Nesbit’s best-written ghost story, and it certainly on par with the likes of Arthur Machen, Henry James, and Shirley Jackson in terms of its stunning prose and unsettling insinuations. It has more literary merit than “Man-Size in Marble” more self-control than “From the Dead,” and more spiritual power than “John Charrington’s Wedding.”

All in all, it is among my favorite haunted house stories – a masterwork that is crying out to be interpreted as a graphic novel or short film – one which has sadly laid dormant and unstudied by scholars and readers alike.

Much like Poe’s “House of Usher” or Jacobs’ “The Well,” this horror story is rich with subtle complexities generated by the dueling polarities of equally-plausible supernatural suggestions and natural explanations. When the horror does come, it is actually rather Aickman-esque: bizarre, unexplained, and disturbing, with hints of some hideous moral crime.

“Unlucky” homes are among the first ghost stories that we have in writing. Pliny the Younger recorded a story about a spirit who haunted a house with clanking chains; the Tower of London is so famous for its ghosts that they are virtually part of the furnishings; “The Fall of the House of Usher,” The House of Seven Gables, The Turn of the Screw, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” The Haunting of Hill House, and The Shining are all considered classics of world literature, even outside of the supernatural genre.

“Bad Places” are symbols of the institutions in life which convey the wickedness of previous generations forward into the future: prejudices, inequalities, and segregations. Houses symbolize the heart of man, and – for a house to be haunted in literature – its previous owner must be guilty of some unatoned sin which society has agreed to ignore (or been incapable of avenging), leaving the moral energy unresolved.

For this reason – like the crimes of a civilization – the house propagates its evil with each generation until someone resists it. Such is the case with the House of Silence – a house where treasures lure and horrors reside.

SUMMARY

In a non-descript time and country, a thief stands on a dusty road looking up at a wall at sunset. “Not the least black fly of a figure” can be seen on either side of the road, which winds in opposite directions. He is alone, and prepares to vault the wall, taking advantage of a gap in the masonry which has been hidden from detection by overgrown trees. Having successfully scaled it, he finds himself in the sprawling rural park of an abandoned manor – his target.

As he nears the vacant lodge-house, he sees the “gaunt griffins” carved on the gateposts – the family crest of the infamous clan whose estate he hopes to raid. Already, as he trudges through the eerily silent woodland, he can see the tall black towers gleaming in the dying sunlight. As he proceeds into the wild, untended gardens, he is unsettled by the life-like female statuary. Suddenly, he is startled by a moving figure in white – but it is only a ghostly peacock.

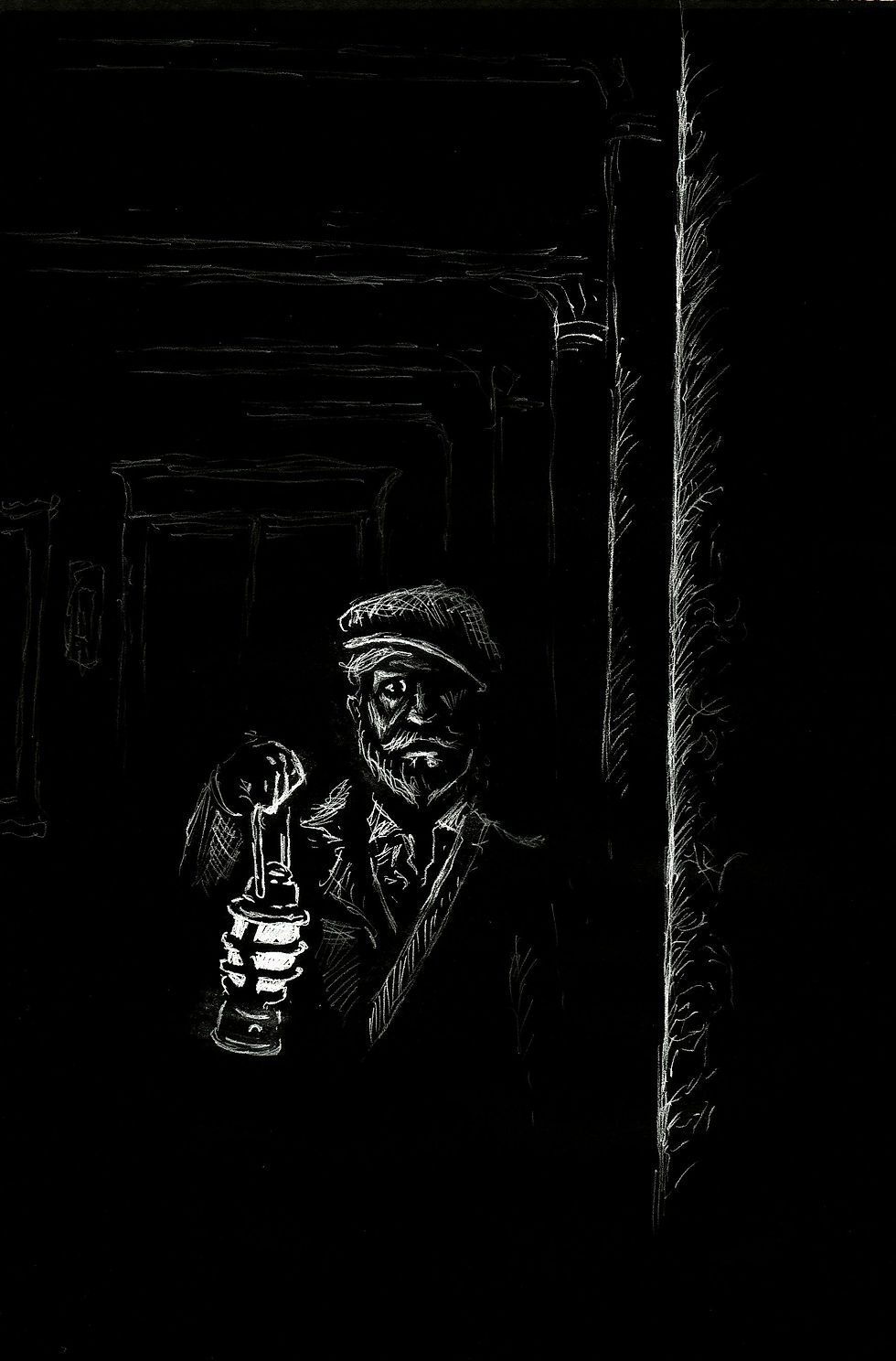

Scanning the eyelike windows, he finds the one he wants – unshuttered and vulnerable – and climbs a nearby tree to reach it. Climbing into the dark room, he pulls out and unshutters a dark lantern, before beginning to prowl the derelict chambers, galleries, and hallways – all now at his unlimited disposal.

He thinks back on how he came to be on this adventure: he had cared for a former servant during his final illness, a man who described the property and its treasures. He begins to talk out loud but is disturbed by the break in the pervasive silence, so he whispers to himself instead.

He repeats the lore of the family with the griffin crest – an animal symbolic of power, wealth, and protection – of how, under the public scrutiny raised by a series of scandals, implied to be sexual in nature – they had abandoned the estate and “gone away none knew whither” although some in the village whispered that “the great man had not gone, but lived there in hiding.”

He dismisses this out of hand, though, because “there is the silence of death in this house,” curiously comparing the oppressive “stillness of the place” to the weight of “a dead man on one’s shoulders.”

Remembering the old servant’s story, he looks for a door with the griffin arms carved into it, encircled by a wreath of roses. He presses the seventh wooden rose, and the handle-less door unlocks and opens. This leads him into “as it seemed… some other house” which dwarfs the elegance of the public side of the manor: this is the patriarch’s secret wing where he undoubtedly hosted his hinted-at orgies, entertained his mistresses, and seduced his conquests. The opulence is overwhelming.

At this point, the thief’s cautious focus begins to transform into something more sinister. He senses a rush of “gaiety of heart, a sense of escape, of security,” now feeling that “the poignant silence … here was no longer a horror, but a consoler, a friend.” No longer afraid, he sees that the dusty chandelier still has dozens of half-burnt candles in its sockets, and he lights them, throwing light over the scene of unimaginable wealth.

He has one final scare in the master bedroom when he finds himself “face to face with a death-white countenance in which black eyes blazed at him with triumph and delight,” only to realize – to his amusement – that he had not recognized his own face in a mirror, distorted as it was with the intoxication of greed and power. He caresses and plays with the finery and drinking expensive wine from a small teacup of pink china – the cost of which, alone, he notes, would be more than a year’s income. Finally, he plunges into the silk bedsheets and is briefly surprised: it smells “as though some sweet woman had lain there but last night.”

Giving this no further mind, he begins to fill his thief’s bag with small objects of silver and jewels, bemoaning that he cannot possibly cart off the furniture or even carry most of the small articles without help (help which would require sharing the bounty with others). Instead, he is driven by bitter malice to smash the mirror and shatters the teacup out of spite (crowing that “No man less fortunate than I, to-night, shall ever again drink from them”). He leaves the candles to burn themselves out with no one to see them.

Now it is time to leave, but he finds that he is lost in the labyrinthine pleasure palace. One door – carved with virginal lilies – mysteriously “opened itself a little” and he goes through it, finding himself in a damp, moldy passageway. Hoping to follow it outside, he suddenly realizes that at some point he began to long to flee from this place, noting that as soon as he shut the secret door behind him, he had just as surely: “shut away warmth, and light, and companionship and once more menaced by the invading silence that was almost a presence.”

He once again feels compelled to “creep softly” and hold his breath at every corner of the maze-like passage “for always he felt that he was not alone, that near him was something, and that its breath, too, was held”

When he finds himself back where he began, he becomes anxious that he may have fallen into a trap, and shivers at the thought of dying like a rat, far from the face of the sun, where – fittingly – his only company would be the literal rats who would eventually consume his corpse.

Happily, however, he finally stumbles upon a door – which leads to another series of corridors – which also finally leads to an exit. The light of dawn is brightening the sky and birdsong fills the air. However, this exit has led to a strange, overgrown, enclosed courtyard “still in damp shadow.” Wading through the “tall weeds… thick and dank” he is suddenly struck by an odd sound that contrasts the songbirds’ warbles: the angry buzz of carrion flies. Now “the presence in the silence came upon him more than ever it had done in the darkened house” in spite of the cheerful morning.

Feeling his way through the weeds, he steps on something he – in terror – at first takes to be a snake: it is not – it is a woman’s braid. The braid is attached to the body of a blonde woman in a green gown, laying dead on the ground. Then the sound surges: “all about the place where she lay was the thick buzzing of flies, and the black swarming of them.”

Having “come into the presence that informed the house with silence” he abandons everything – lantern and thief bag included – and runs blindly back into the corridor, guided somehow by “the horror in his soul.” Fear seems to be wiser than greed, because he rapidly locates the single door of escape, bolts it behind him, and charges through the hallways, through the garden, through the park, past the lodge, over the wall, and back onto the road, which – once again – has “no least black fly of a figure” stirring on them in either direction. Which one he chooses is not mentioned, but he never looked back…

ANALYSIS

The House of Silence is a House of Sin – one which shelters wickedness and ordains death. There are two ways of interpreting this story: one based on the literal plot and one founded in the suggestive atmosphere. To first time readers, the former is the most pressing one (“who was the corpse and why was it there?”), and while this interpretation is ultimately far less important than examining the emotional impressions given, we can begin there.

Nesbit – as in “The Mystery of the Semi-Detached” – exerts a great deal of commendable self-control in this story, offering no definitive solution to the riddle of the body consumed by flies, but we have some clues. The family of the house has disappeared for unknown reasons, although it is rumored that “the great man” still lives on the estate like a fugitive. This implies that some horrible crime or crimes may have been committed (either by the family itself or by the “great man” specifically).

When the thief presses his face against the sheets, he is surprised to find them fresh and fragrant – “scented delicately as though some sweet woman had lain there but last night.” This is a particularly telling phrase since it implies that a woman of flesh and blood was bedding in the sheets less than twenty-four hours ago. As with so many of Nesbit’s stories, there is a potent eroticism about the detail, particularly in the word “lain.” There is both a suggestiveness about the term (a euphemism for sex) and a voyeuristic quality to the thief’s fantasy of “some sweet woman” whom he pictures in the bed that he is currently pressing his skin against.

When the thief finds the body, it is still fresh, which is to say it still has skin and eyes and hair, but it has been dead long enough to attract hordes of carrion flies – roughly a day or two, or precisely long enough for the woman to have been bedded the night before. The fact that she wears a braid implies one of two things – either she is very young (braids were worn by younger women, especially single women) or that she was ready for bed (many women braided their hair before bed to keep their long hair controlled during sleep).

Either option has a suggestive nature. What we are left with are a few possibilities: if the corpse is real – that is, not a ghostly vision (cf. “Semi-Detached”) or a gruesome manifestation (cf. M. R. James’ “Martin’s Close,” F. Marion Crawford’s “The Upper Berth”) – then we might suspect that the family fled their home due to the scandals of its patriarch (scandals which may have been sexual, violent, or both), but that he has indeed remained behind in his palace of evil, that he had only the night before seduced or raped the dead girl, and that shortly after he killed her, or she killed herself.

The fact that she is found in the courtyard which the thief finds in his attempt to leave the building might imply that she was also trying to escape – running for her life. If the corpse is a ghost, then we might assume that the fragrance on the bed was also ghostly, and that the corpse is that of a woman whose death was the original cause of the family’s flight (again, probably at the hands of “the great man,” who may not have stayed behind, although his spirit seems to have).

As a final word to this interpretation, I cannot be wholly confident in this analysis, but my instinct is that Nesbit is showing us the body of a recent victim of a brutal date rape, and implying that the wicked patriarch of a shamed family still uses the old home as his base of operations.

II.

This leads us into the more nuanced analysis of mood and theme. The thief is himself lured to the home by promises of riches and wealth, and he is at first dazzled by what he finds. It is a fine home, and he wishes that he could own it or at least the possessions therein. He lusts over the opulence and admires it approvingly, only to be traumatized when he realizes what its elegance has allowed to be concealed.

The mood waxes from anxious curiosity, to awestruck delight, to lusty greed, to unsettled concern, before vaporizing in a thermal-flash of moral horror. As I mentioned in the opening notes, haunted houses are emblematic of a society or a person with a secret sin. This house (which could be easily read as an allegory for the spurious legacy of wealth and left behind by the bygone Victorians) has gone unquestioned because of its grandeur and affluence, and yet – behind the curtains – great sins are left unseen and uninvestigated, often knowingly.

It certainly seems to me that Nesbit is critiquing the double-standards of her and her mother’s generations whereby the dodgy behavior of “great” men were often left unchallenged and unquestioned simply because of their influential status and material success. The thief is drawn to the opulence of the great house and fantasizes about becoming master of it; he envies the man who could claim such extravagant wealth up until he realizes what that wealth has been used to justify. There is even the chilling detail of his encounter with the mirror at this juncture, where he frightens himself at first because he doesn’t recognize his own face due to his ghoulish expression – “a death-white countenance in which black eyes blazed at him with triumph and delight” – which almost sounds like a man on the brink of possession.

Indeed, he is seemingly guided down the corridors by a patron-like, male presence: a persona who seems ever at his side – holding its breath when he holds his – and inviting him to become his apprentice in villainy. The thief is struck by the peculiar simile “it is like a dead man on one’s shoulders,” and perhaps he is hounded by such a spirit, or spirits, of the absentee master, or masters, whether or not they are living or dead.

III.

At the heart of this story, I can’t help but sense a feminist message that cries out accusatorily against the “great men” of Nesbit’s society and powerful patriarchies that ravage colonies, industries, slums, and economies but are themselves left gently unmolested about their wrong-doings. While the literal plot of the story may follow – like “The Semi-Detached” and “Man-Size in Marble” among others – the problem of sexually-motivated murder, the larger picture appears to be an indictment of the broader British machismo, capitalism, cronyism, and classism.

The House of Silence is silent because no one talks about it. No one questions it. No one resists it. It is a society gone silent – a nation at odds with its conscience, muted by awe and gagged by vain respect for status and privilege. Nesbit’s thief is at first enamored by the status of his unseen guest, but at the heart of the estate (literally – and with symbolic import – at the very center of the mansion) he realizes that it has all been a Bluebeard’s castle.

And such might be said of Edwardian England: magisterial and majestic, powerful, and princely, yet behind the regal façade lurk unnoticed crimes of power. In the end, the thief refuses to be a “fly”: the final lines compare human beings with flies – mindless sycophants that feed off of misery and tragedy – and it is fitting to think of the thief as a fly himself: an amoral renegade who hopes to nurse himself on the luxury of the well-off.

But seeing the corpse blackened with flies is an indictment of his own complicity in this societal sin, and he leaves both his loot and his burglar’s tools behind. No longer wishing to be a fly on the carcass of the oppressed, he leaves it all behind – the stinking cadaver in the tall grass, and the House of Silence, a house not haunted by bangings and moanings and rage, but by collective denial, passive allowance, and silent permission.

I always trust Space Waves, a free game platform for all ages. With its basic but fascinating action, space waves will keep you focused and striving to conquer each one.

Not only does Scratch Geometry Dash feature levels created by RobTop, but it also allows users to create their own levels and share them with others, offering endless opportunities for creativity and challenge.