Carnacki the Ghost-Finder & The Hog: A Detailed Summary and a Literary Analysis

- Michael Kellermeyer

- Feb 14, 2021

- 10 min read

Updated: Jan 11, 2024

Swine feature prominently as villains and motifs in Hodgson. Sometimes they are antagonists outright, othertimes they are instruments of the plot, or used to describe the attributes of Hodgson’s horrors (more simply put, they are either monsters, victims of monsters, or used to describe monsters). This is most prominently featured in “The House on the Borderland,” where a lonely man is besieged by porcine demons, his house accidentally having been built on a soft spot in the fabric between the natural and supernatural worlds. Those devils are extremely similar in form, character, and motive to those which haunt Carnacki’s client in “The Hog.”

The story itself is something of a reworking of J. S. Le Fanu’s “Green Tea,” a mystery featuring Carnacki’s ancestor, the occult specialist Dr. Hesselius. Hesselius comforts a minister who is being hounded by the tyrannical specter of a black monkey – a libidinous despot whose mission seems to be driving his host to suicide. Like Carnacki, Hesselius was an old hand at occultish mumbo-jumbo, and bloats the otherwise scintillating plot with his pseudo-scientific theories (namely that his client’s persistent use of green tea – then feared to be more addictive and stimulating than black coffee, often laced with additives and stimulants – had opened up his “third eye”).

The monkey is very similar, symbolically, to the hog. Both animals have a great kinship to mankid (monkeys being our ancestors, pigs have human-like anatomy which allows us to use their organs) – specifically the darkest and most bestial elements of our species. Monkeys are notoriously vain, impulsive, violent, libidinous, despotic, and delusional. They are used to symbolize mankind’s self-importance – our intelligent faults. Hogs, on the other hand, are used throughout folklore and literature to represent our basest, most shameful traits – stupidity, herd mentality, self-indulgence, corpulence, lack of hygiene, lack of shame, lack of control, gluttony, rage, fear, greed, envy, lust, and arrogance.

Many faiths across the world ban the eating of pork due to this very association. They appear as caricatures of human appetite and ignorance in “The Three Little Pigs,” the myth of Circe, “Animal Farm,” and Pink Floyd’s “Animal” ablum. Christ tellingly cast Legion – the vast demonic horde possessing the madman in the synoptic Gosepls – into a herd of swine which then collectively went insane and charged off a cliff into the sea. Hogs have frequently been associated with demonic possession and Satanism ever since, making sinister appearances in “Lord of the Flies,” “The Amittyville Horror,” and “Spirited Away.”

Like Le Fanu’s Monkey, Hodgson’s porkers are deeply symbolic – especially to him – of human weakness. Hodgson was a committed germaphobe and found great strength in his self-control. To him, pigs represented everything he tried to banish from himself and everything he resented and feared within him. The story is one of possession, but it is also one of complex cosmology, and has been called Carnacki’s greatest case by many if not most scholars. Brian Stableford gushed of the piece claiming it to be “by far the best [of the Carnacki stories” and “another visionary fantasy in which the metaphysical realm is dark and hostile, inhabited by degraded and malevolent entities whose porcine attributes mock human ambition.” The spirits are not piglike naturally, but appear to their tormentors in such a shape. To Hodgson – who found his much beloved control in self-discipline and saw its antagonist in self-indulgence – this confrontation would be his worst nightmare. It certainly was Carnacki’s.

SUMMARY

Carnacki gathers his friends, as usually, to tell them another story about his most recent adventure beside the snapping fireside of his London study after a rich meal washed down with port. Amid the cigar smoke, he tells of his latest client, a man named Bains whom he fears may have a breach in the metaphysical barrier which usually protects humans from the intrusions of the “Outer Monstrosities.” Bains has been suffering from terrifying lucid dreams that have disturbed him for months. He finds himself in a “deep, vague place” with shadowy threats lurking on all sides in the dark.

He instinctively knows that it is a bad place which he must escape at all hazards, and struggles to regain consciousness before the great threat that he senses awaiting him can lunge out. He manages to force himself back awake, but finds himself experiencing what we would call sleep paralysis: his body is immobile and although he can see the mortal world, his dreaming world seems to have burst in on his waking world, and as he lies there in terror, he is aware of distant sounds of a gigantic swine squealing and grunting. He finally manages to get up and fully awaken, but he is constantly haunted by the random screams of a frantic hog. What is it? Why is it coming for him? What can be done?

Carnacki prepares his strategy of attack and Bains agrees to be completely submissive to Carnacki, creating an unwavering power structure between them (which will quickly prove suspiciously erotic). Committed to their course of action, they begin to set up Carnacki’s Tesla-esque paranormal machinery in the room where they will conduct their first experiment. The main apparatus is his spectrum defense – seven concentric rings made of neon tubes which range in color from red, orange, and yellow, to green, blue, indigo, and violet – essentially a rainbow-colored ring of neon light. The extreme ends of the color spectrum – red and violet – attract the most powerful, most evil entities, whereas blue – the median – attracts positive supernatural powers. Carnacki will attempt to lure Bains’ demon out of hiding – to identify and target it for destruction – with the outer, flame-colored lights, while relying on the cooler colors on the inside to act as a defensive fence.

***

As they prepare the begin the experiment, Bains shamefully shares with Carnacki some new information: not only has he been hearing the swinish grunts, but he himself has been squealing like a pig in response to them. Carnacki is disturbed by the implication he reads into this, but they proceed by donning rubber suits and helmets and having Bains lie down on a low table with glass legs set in the center of the neon rings. Carnacki plugs electrodes into Bains’ helmet and asks him to do two things: focus his thoughts on the sound of the squealing hogs, and stay awake at all hazards – he is to replicate his sleeping conditions without actually falling unconscious.

Like any great paranormal detective, Carnacki sets about using a camera and phonograph recorder to try to capture spectral sights and sounds, and he is soon able to record the vague sounds of a swarm of squealing pigs regularly peppered by the monstrous grunts of what sounds to be an inconceivably gigantic hog. The intensity of the sounds is more powerful than Carnacki expected, and furthermore, he is horrified to note a growing shadow spreading beneath Bains’ table in spite of the piercing neon light and lack of obstructions. Carnacki commands Bains to stop focusing on the sounds so intently, but it is too late: Bains has fallen asleep.

Bains’ eyes are peeled open – agape in unconscious terror – and he begins grunting and squealing with piggish glee. The shadow grows, darkens, and deepens, and the two men begin to sink into what appears to be the mouth of this otherworldly pit.

Carnacki scoops Bains up in his arms and holds onto him as the shadow spreads outward, causing them to back up against another strange phenomenon: a force field that rises surrounds the entire neon apparatus in the form of gyrating, black funnel cloud. Carnacki pricks Bains’ skin to draw blood in an attempt to attract his AWOL soul, but he forgets that blood can also attract the “Monsters of the Deep,” and as the evil powers increase in violence, Carnacki lugs Bains’ rigid body out of the heart of the neon rings and stands between the violet and indigo circles where he hopes to be protected by the benevolent supernatural powers drawn to that end of the spectrum.

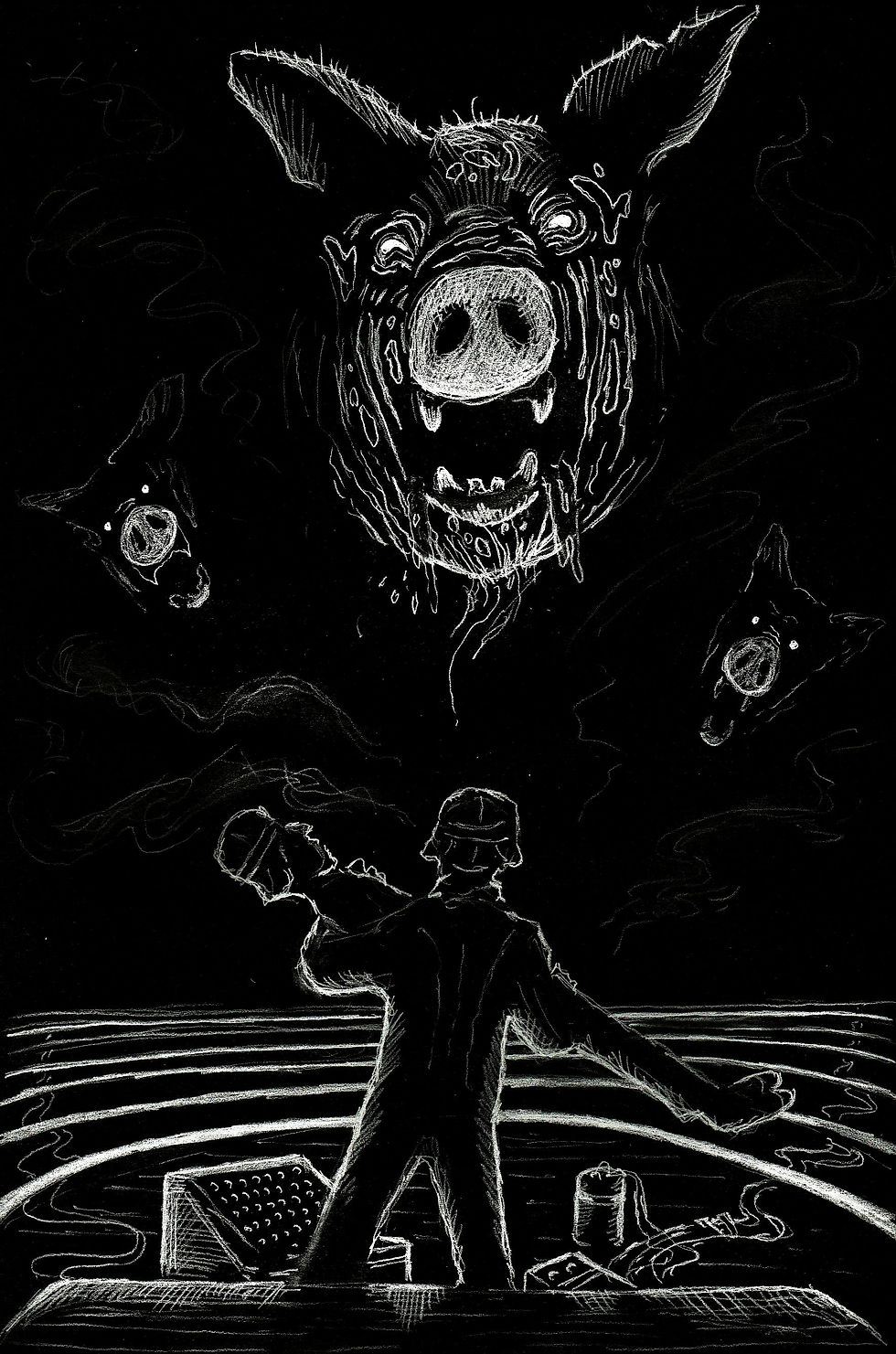

At that moment, the room is rocked by an explosion of supernatural squeals and grunts emanating from the pit in the center of the room, followed by the appearance of a glowing spot that rises from its depths, growing in size and clarity into the form of a gigantic, detestable hog’s face. Snorts and squeals begin echoing from the funnel cloud surrounding them, and – wedged between the swine sounds in funnel and the Swine Thing in the pit – Carnacki seriously considers using his revolver to kill Bains and himself.

Carnacki now realizes that this gigantic Hog looming above them is the manifestation of an entity referred to as the “Outer Monstrous One” in the Sigsand Manuscript (a metaphysical tome which is to Hodgson as the Necronomicon is to Lovecraft) – an evil elemental that once reigned over the world and is now using Bains’ mind to restore itself to power. Having realized this, Carnacki temporarily shelves his plan to commit suicide: he must do anything possible to save humanity from this unexpectedly powerful threat.

Grabbing the blue neon ring with one hand and collaring Bains with the other, he advances towards the funnel cloud wall, which recedes from the heaven-hued light, causing the Hog to evaporate in power. At first Carnacki imagines they have found a key out of their predicament, but the Hog immediately fights back by bodily possessing Bains, who wrenches out of Carnacki’s grasp and falls on all fours, squealing lustfully and scuttling towards the Hog’s half-faded form. But Bains cannot cross the barrier of the blue ring, and is trapped inside it with Carnacki, who overpowers him, tying him up with his own suspenders.

Furious, the Hog – its face melted away into a single, glowing eye and snout – advances on the outermost (violet) ring, causing it to disintegrate, before attacking the indigo ring (the last band left before the blue one that is protecting the two men), but they are unexpectedly protected by a second, great power – manifested by an otherworldly dome of blue and green light which immediately breaks the spell, causing the funnel cloud, pit, and Hog to vanish.

Exhausted and relieved, Carnacki has no more patience for Bains: he hypnotizes the now-wakened client (who was convinced that it was all just another dream), and commands him to immediately wake up if he is ever plagued with dreams of the Hog again, preventing him from descending into the deep, lucid dreaming that the Hog was depending on to allow It to cross from Bains’ consciousness into the mortal world. Looking around them, Carnacki sees the only evidence of their metaphysical battle: the indigo ring has been broken, and the violet tube has been entirely melted.

***

The story resumes with Carnacki sipping port beside the snapping fire while his friends look on in stunned disbelief at his wild and bizarre story. They are full of questions, but his best explanation is as follows: the earth itself is enclosed in concentric spheres which correspond metaphysically to the seven neon rings, and each sphere is inhabited by unique supernatural powers with unique appetites and desires. The farthest sphere extends nearly ten million miles away from the earth, and is home to entities like Hog who feed off of the souls of other entities (like humans and weaker spirits) with the ultimate aim of growing powerful enough to consume them all. Carnacki’s guests are deeply troubled – and confused – by all of this, but he is tired of lecturing and it is time to go: “Out you go!” he says – as always – and they file out into the quiet, dank dark of the London night.

ANALYSIS

Carnacki’s final case (from Hodgson; he continues to be prolific in pastiches and fan fiction) is probably his most complex and most spiritually terrifying. There is more of a glimpse of the cosmic sublime in this story than in any of Hodgson’s short stories. It comes closest to touching the existential terror of “The House on the Borderland” – a smiliarly themed nightmarescape with a powerful sense of infinity and the vast oblivion of space. In such a world mutated humanoids and weed-choked deserts take a backseat.

While it has its flaws – among them the widely panned pseudoscientific ending that serves as an anticlimax to its staggering first two acts – the story puts Carnacki farther on his heels than any other tale. For once he looks small, for once he earns out pity, for once we long to look away and leave him to the fate his hubris has brought him to. We have a sense that he has been dodging this bullet for a long. There is a vastness, a cosmic power to “The Hog” that dwarfs the ghost-finder in a way that easily eclipses his Holmesian charisma, making him more of a thunderstruck Lovecraftian protagonist than a charming maverick. In his extensive essay, “Ye Hogge: Liminality and the Motif of the Monstrous Hog in Hodgson…” Leigh Blackmore offers the following analysis of “The Hog’s” blood-chilling defiance of supernatural clichés:

“While Carnacki uses occult equipment in his defenses against monstrosities (including swine-things), and while he recognizes their potential spiritual as well as physical malevolence, he ultimately uses his scientific intelligence to define the monstrosities as blind cosmic forces. These forces, including the hog-things, are phenomena which are, perhaps preternatural (i.e. strange or abnormal phenomena that seem to violate the normal working of nature), but not necessarily supernatural (i.e. incapable of being explained by science or the laws of nature).

“Thus the alien forces that Carnacki dubs truly inimical to the human species, though the author of the Sigsand Manuscript saw them so, and though Carnacki himself may be tempted to. Rather, like Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones, these forces, though horrible, are indifferent though to humankind – vast beings whose motivations are entirely incomprehensible to human beings. To us – certainly to Carnacki – they appear ‘evil’; but this is due primarily to the sanity-blasting tendency of such forces to reveal humankind’s puniness in an ultimately indifferent universe.”

Indeed, the existential cosmicism of “The Hog” comes profoundly near to Lovecraft’s most astronomical fiction (e.g., “At the Mountains of Madness,” “The Shadow Out of Time”). Its vision of a vast, antihuman spiritual atmosphere certainly places Hodgson ahead of his time in the company of the likes of Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, Oliver Onions, and Arthur Machen, who specialized in horror which extends beyond the confines of space and time. Regardless of when it was written, its traditional role as Hodgson’s “last story” is somewhat fitting: it opens up a window into the extensive, punishing universe that so much of his short fiction attempted to manifest, however imperfectly – the enemy of mankind, the foil to human dignity and ambition, the vast, grinning face of oblivion.

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

google留痕 google留痕;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

온라인 슬롯 온라인 슬롯;

온라인카지노 온라인카지노;

바카라사이트 바카라사이트;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

google seo…

03topgame 03topgame;

gamesimes gamesimes;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS Machine…

EPS Machine…

seo seo;

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger…

seo优化 SEO优化;

bet bet;

google seo…

03topgame 03topgame;

gamesimes gamesimes;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS Machine…

EPS Machine…

seo seo;

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger…

seo优化 SEO优化;

bet bet;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

google 优化 seo技术+jingcheng-seo.com+秒收录;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群

gamesimes gamesimes;

03topgame 03topgame

EPS Machine EPS Cutting…

EPS Machine EPS and…

EPP Machine EPP Shape…

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

EPS Machine EPS and…

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

谷歌seo推广 游戏出海seo,引流,快排,蜘蛛池租售;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

gamesimes gamesimes;

站群/ 站群

03topgame 03topgame