E. Nesbit's Man-Size in Marble: A Detailed Summary and Literary Analysis

- M. Grant Kellermeyer

- Jan 7, 2019

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 9

Edith Nesbit’s supernatural masterpiece – “Man-Size in Marble” – was first published in 1887, one year after “Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde” and three years before The Picture of Dorian Gray. It was a period of intense revival for both popular and literary horror, one where the tropes of terror were regularly being reworked in surprising and unsettling ways, communicating completely different ideas and pondering the younger, more cosmopolitan Late Victorians’ unique anxieties. Nesbit was something of a poster child of her generation – one defined by its shaky relationship between modern ideals and a nostalgic ennui for the pre-industrial past. As such, her horror stories reflect the era’s fascination with the uncanny, liminal spaces, and the anxious, cognitive dissonance between the bourgeois, Belle Epoque present and the agrarian, Early Modern past.

The late 19th century saw a revival of ghost stories, fueled by the tension between breakneck scientific progress at odds with timeless spiritual needs and imagination. “Man-Size in Marble” taps into this cultural atmosphere, blending the eerie traditions of rural folklore with the rational skepticism of modernity.

At its core, the story explores themes of superstition versus reason, the fragility of human security, and the hidden dangers that lurk beneath seemingly peaceful surroundings. Through a vividly drawn English countryside setting, Nesbit crafts an atmosphere of creeping dread, where local legends carry unsettling weight. The tension between skepticism and belief plays a central role, as the protagonists find themselves caught between rational explanations and inexplicable occurrences. The tale’s psychological depth and atmospheric buildup make it a standout classic in the Gothic tradition.

II.

Nesbit’s own life and literary influences seep into the fabric of the story. Raised in a time of spiritualist movements and scientific discoveries, she was deeply aware of the Victorian fascination with the interplay between history and the supernatural. Her personal experiences—marked by financial struggles and an unconventional lifestyle—also shaped her fiction, lending it a unique emotional realism.

“Man-Size in Marble” echoes the storytelling traditions of the mid-Victorians (e.g. Rhoda Broughton and J. Sheridan Le Fanu), while presaging the work of the Edwardians (e.g. M. R. James and W. W. Jacobs), with its slow-building suspense and chilling ambiguity. Unlike the bookish James (but very much like his fiery-minded idol, Le Fanu), Nesbit’s grim ghost stories almost always involve a sexual tension and frustration as a major theme.

They typically follow an estranged couple struggling to understand one another, an explosive love triangle, or an impulsive affair between suspicious lovers. They are torn between desire and distrust, between fresh passion and sexual boredom. But that is not the case in her most famous story – of any genre – the brilliant, traumatic “Man-Size in Marble.”

While Nebit’s leading couples in the far majority of her stories are clouded in disapproval and scandal, these spouses are cozy, charming, and romantic: they are two genuinely loving, relatable spouses, still snuggled together in a honeymoon mentality. Pet names like “wifie” and “dearest” and the petty anxieties of domestic concerns such as blacking boots and cleaning dishes make this country setting vastly different from the urbane West-Enders. But chaotic hazards menace their love-nest. Failure to take heed of sincere advice – even to the slightest degree – Nesbit suggests, can rob us of all we hold dear, leaving us wiser but sadder… if we manage to survive. Nesbit constructs a universe in chaos, one deaf to entreaty and blind to love, a heartless, merciless cosmos that crushes hope and smothers love.

SUMMARY

The story follows two newlyweds who have begun renting a cottage in southern England in order to escape the bustle of the city. Like a pair of modern hipsters, they love travelling the less-trafficked road: eschewing a conventional apartment for a rustic stone house, where the wife, Laura, writes fiction and her unnamed husband, an artist, paints. They are deeply in love and tremendously happy together, and the rural beauty surrounding them seems to reflect their marital bliss. Soon after they arrive in their new town, they hire a housekeeper and settle into their artsy, bohemian life. It isn’t long after this, however, that the housekeeper quits unexpectedly, upsetting Laura. To calm her down, they go on a moonlit walk through the waving grasslands and find themselves arriving at an ancient Norman church.

Walking through the doors they study the centuries’ old architecture. In particular, they are drawn towards two marble, funerary statues of cruel-looking Norman knights. The narrator notes that he has heard that the two men were renowned for their cruelty and depravity, that they had an evil memory in the area, and that their house – long since destroyed by providential lightning – originally stood where his little love-nest currently sits. Pacified by the cold moonlight and the solemn church, Laura agrees to go home.

Soon after, the narrator meets with the housekeeper to discuss her reasons for leaving them, and is surprised when he learns that a local superstition holds that the two knights are said to rise from their tombs – in the form of their marble statues – and return to their manor on Halloween night. As it is almost October 31st, she refuses to stay with them until after the fateful night. Before leaving, she urges them to leave the house on All Saint’s Eve, to lock the doors, and adorn the openings with crosses. Concerned about his wife’s delicate mental health (she is fairly high strung and excitable), he keeps this story to himself.

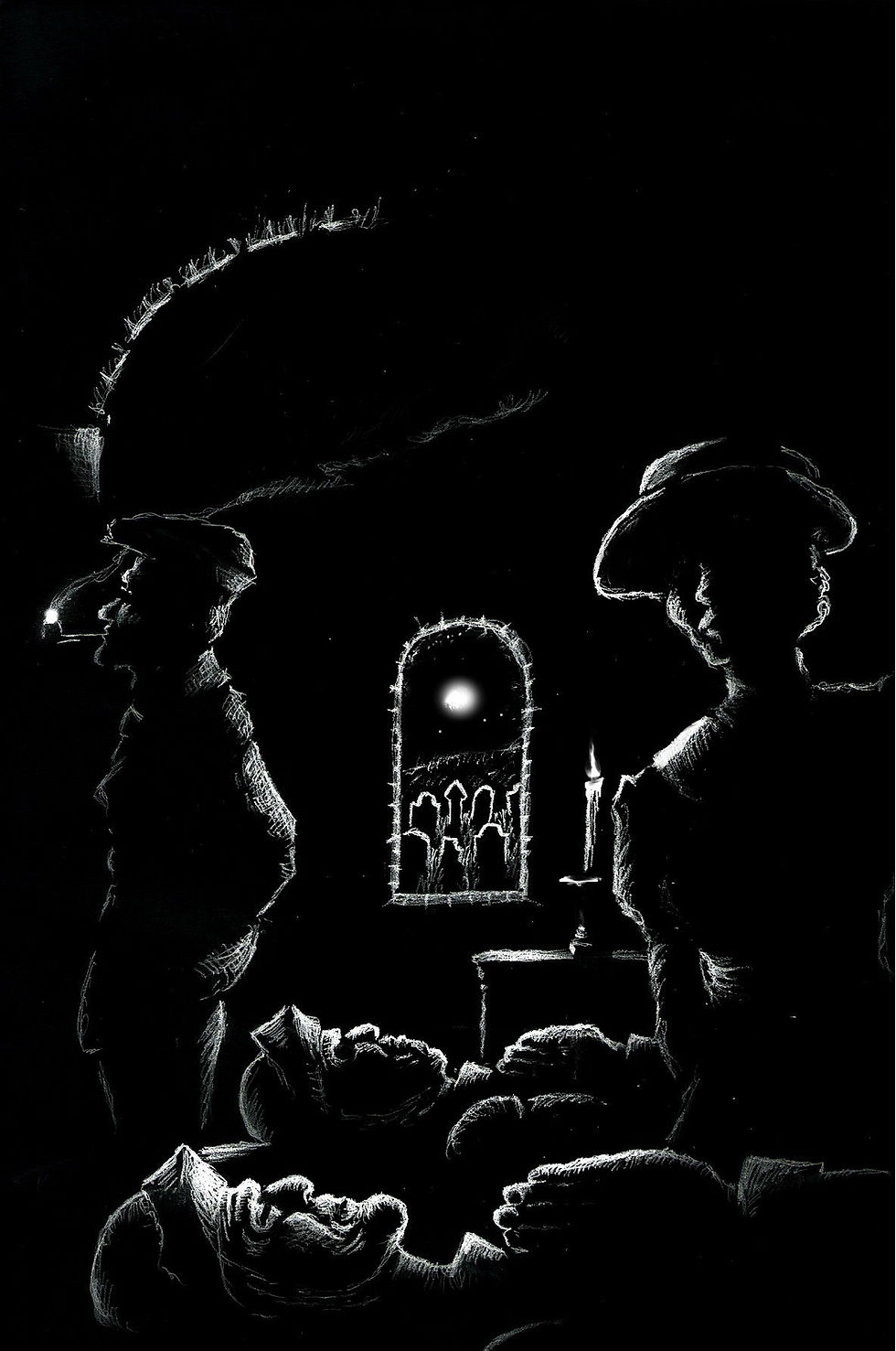

On Halloween Night Laura seems tremendously distracted, claiming that she is afraid and has a premonition of approaching evil. She clings to her husband for security, but he brushes her worries off and sends her to bed early when it becomes clear that anxiety is exhausting her. The countryside is drenched in moonlight, and he decides to go on a walk to the church, smoking his pipe and absorbing the autumnal beauty. When he arrives at the church he suddenly remembers the legend, and while at first thrilled by the thought, he is suddenly terrified when he sees the knights’ marble tombs are missing their statues. He races back home but is stopped by a neighbor, a doctor, who ensures him that he is overreacting to a trick of moonlight. They walk back to the church where, by a match light, they confirm that the statues are in place, although one seems to be missing a finger – a new development.

Satisfied by still excited – and now preternaturally worried about his wife – the narrator goes back home, only to find the door open. The place is blazing with candles, lamps, and improvised tallow lights – anything to drive away the darkness. They find Laura flung across a table – dead and disheveled, with a wild look of horror on her face. In her clenched, cold hand they find a marble finger.

ANALYSIS

Regardless of its advances – of science and civility, manners and law – society remains vulnerable to the same ruthless passions which prowled boldly through it during its degenerate infancy. When she included “Man-Size in Marble” in her 1893 anthology, Grim Tales, Nesbit created a thematic counterpart for it – “The Mystery of the Semi-Detached” (wherein a playboy slips into his lover’s apartment at dusk only to be terrified by a gruesome sight in her bed), to similarly illustrate the anonymous evils that can brew in the heart of bustling, urban affluence, and sent that shellshocked protagonist packing for the simple domesticity of the English countryside.

In this earlier tale (which, like “Semi-Detached,” was influenced by Rhoda Broughton’s “Behold, it was a Dream,” which tells of a premonition that foretells the gruesome murder of newlyweds in their rural cottage) she tears the idyllic mask from a rural retreat, exposing a dormant misanthropic energy, ripe with thoughtless lust and bursting with psychopathic glee. The couple is sweet and careful, selecting their honeymoon cabin with precision and mindfulness. Their lives are frugal and sensible, yet still tenderly romantic. They are the very embodiment of tidy, middle-classed Englishness, which so-carefully merges pragmatism with aesthetics. Their world is purposefully manicured, and yet the sky above their caring kingdom is torn to shreds, and evil things leer through and crush them. Nesbit’s universe is harsh, sudden, and sadistic, and haunted by the wickedness of mankind; though six centuries have passed since their atrocities, the spiritual shadows of these rapacious knights still darken the leafy footpaths of their parish. They do not represent a mythic or godlike evil, but one real, tangible, and contemporary – man-sized sins that beat in men’s hearts and stew in their brains.

II.

There also dwells in this story a moral sentiment which is prominent in the works of Poe, especially “The Oval Portrait.” Both stories feature an artist who adores his wife’s spirit – what she represents to him as a spiritual ideal – but fails to appreciate her complex humanity – her insecurities, psychological needs, and fragile mortality. It isn’t until the moment when the artist most needs the complex personality of his wife that he arrives to find her dead – wasted and used up during one of his reveries.

Both men understand only too late that what we value most is that which is rarest and most finite: life, shared love, mutual affection and experiences – an ideal can live forever, and a portrait may outlive generations, but a life lost is a treasure destroyed. Nick Freeman appears to concur with this interpretation, viewing “Man-Size in Marble” as a feminist tragedy. The following excerpt comes from the critical anthology Women and the Victorian Occult – a highly recommended read:

‘[It] remains a disturbing story more than a century after it was collected in Nesbit’s bluntly titled Grim Tales… There is certainly no suggestion of a protecting Providence overseeing the innocent Laura as there was in many earlier Victorian ghost stories. The clergy are conspicuous by their absence, and Jack’s belief that his wife’s sweetness means ‘there must be a God […] and a God who was good” is the sourest of ironies. The suggestion of symbolic rape makes the story all the nastier, with Laura still clutching the phallic finger while her hair lies “loosened and fallen to the carpet.” Clearly she spent her last moments in an agony of terror as the statues disregarded her protective candles and burst into the cottage. Why, then, if Nesbit can be regarded as a writer of feminist Gothic, does Laura have to die? …

‘In constructing a relationship in which male and female roles seem to be governed by the stereotypes of the day despite her characters’ bohemian pretensions, Nesbit is exploring the consequence of a crude essentialism which configures men as rational and dynamic and women as “sensitive” and passive. Jack clearly should have paid heed to Laura’s anxiety and learned from it, but he allows himself to dismiss it as “nervousness,” recasting a psychic gift as a quintessentially feminine ailment of the day… Nesbit … kills Laura not to punish her but to demonstrate the latent violence inherent in the sexual politics of the period…

‘By injecting Gothic fantasy into what seems at first an unexceptional tale of wedded bliss, Nesbit is able to provide both the shock expected of the genre, especially in short stories, and imbue her fiction with an underlying sense of ideological dissatisfaction. Sentimental aesthetics and rationalistic doctors are just as liable to oppose or inhibit the radical woman’s selfhood as the ghosts of the past, even if they balk at rape and murder.’

III.

Nesbit is not alone in her use of this trope: we see it in Bram Stoker’s Dracula where Lucy and Mina – a self-avowed “New Woman” – are punished by every man in their lives (fiancées, husbands, friends, doctors, and relatives, not to mention the Count), and in the myriad versions of the “demon abductor” myth: Le Fanu’s “Schalken the Painter” (a girl is prostituted by her uncle to a living corpse)’ E. F. Benson’s “The Face” (a girl’s recurring nightmare of abduction comes to fruition); Charles Dickens’ “To Be Read at Dusk” and Broughton’s “The Man With the Nose” (both of which follow a respectable woman’s helpless kidnapping by a possibly supernatural molester); Fitz-James O’Brien’s “The Bohemian” (a man is so consumed with social climbing that he is tricked by a mesmerist into relinquishing his fiancée’s soul to him); and Arthur Machen’s Great God Pan (a mad-scientist drives his maidservant insane after conducting an experiment on her – one which exposes her to another dimension, resulting in her rape and pregnancy by an invisible attacker).

Late Victorian literature frequently mulled over the many possible tragedies which could result from the systemic sexism of any society that reflexively distrusts, dismisses, and devalues the perceptions of women, and “Man-Size in Marble” – savage, haunting, and poignant – remains one of the purest examples of this study.