One of James’ darkest tales – exceeding “Romance of Certain Old Clothes” and rivalling Turn – “Owen Wingrave” has been his second-most commented upon ghost story, surpassing even “The Jolly Corner,” and shares the distinction with Turn of the Screw of having been made into a compelling opera by Benjamin Britten. The antithesis of the cycle-breaking Sir Edmund Orme, the spirits who haunt “Owen Wingrave” are hell-bent on preserving a ghastly, centuries-long pattern of destruction. The story was inspired when James – who was reading the autobiography of one of Napoleon’s generals, and was at the time consumed with visions of glorious victories and gallant defeats – shared a park bench with an attractive young man: “A tall quiet studious young man had sat near him and settled to a book with immediate gravity.” Struck by the juxtaposition of the two things – the violent glories of battle and the gentle beauty of the young reader – James envisioned a world where his pretty companion was thrust into a predestined relationship with war. “Owen Wingrave” is predictably riddled with homoerotic subtext, particularly in the relationship between Owen (whose name means “young soldier,” and whose morbid surname underscores his family’s celebration of wartime death), and his military tutor, Coyle.

Further queer elements exist between both men and the child-like (albeit stupid) youth Lechmere, and with Owen’s war-hungry on-again-off-again girlfriend, Kate (whom Coyle describes as a “brute,” and whose bloodthirsty machinations may or may not be designed to lure her lover to his death). Owen is depicted as a sensitive, poetry-reading, big-souled lad – a boy whose intellect and spirituality has (in Coyle’s mind) far surpassed that of his war-loving family members. Coming from a military family, his refusal to complete his martial education arouses the disgust of his family, his girlfriend, and his ancestral manor. The story begins like a comedy of manners, or even as a Shakespearean romance: a youth must defy his family in order to pursue his heart, and is beset by a number of trials before he can achieve his desires. Indeed, the first three chapters allow us the hope that this is a gentle comedy with a happy ending. But when the fourth chapter arrives, hope is rapidly lost. We venture into the Wingrave house – said to be haunted by his violent ancestors – and we see how Owen has aged after mere weeks. The family is determined to protect its martial lineage, and Owen’s dishonor cannot go unpunished. And yet, there is a twist – one that Coyle finds stirring and spiritual: Owen’s very defiance of his military future is in every way the behavior of a soldier. He is brave, manly, determined, self-possessed, and brimming with gallant character. His seemingly inevitable assassination is therefore wrought with irony: for refusing to be a soldier, Owen will face death in a manner that can only be described as soldierly.

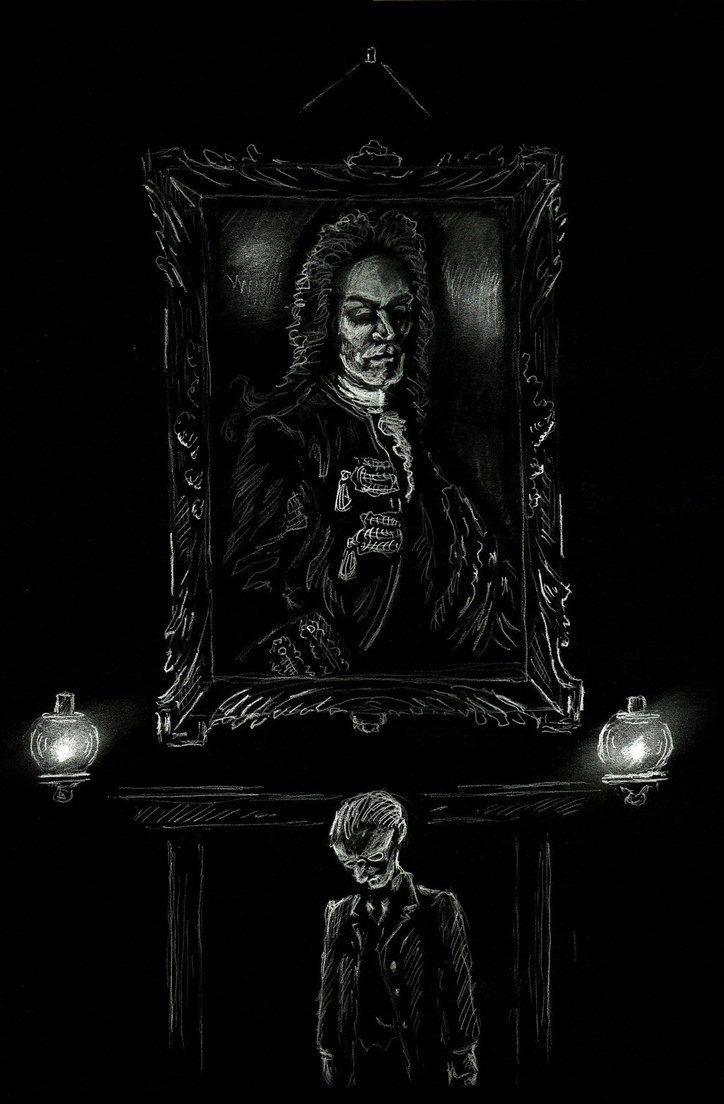

One of James’ most popular stories, period, this is also one of his most Gothic (“Ghostly Rental” and “Romance of Certain Old Clothes” also share its spooky mood. The story follows a romantic youth from a military family, the charming Owen Wingrave (his first name means “young soldier,” and his surname hints at how his family views death in battle – as an achievement). His military tutor is tasked with informing his family that Owen no longer wants to be a soldier, sending his elderly relatives and Spartan fiancée into an uproar. The tutor – hinted at being infatuated with his pupil – is at first aghast (the lad has taken to reading poetry and spurning military obedience for intellectual reasoning), but becomes increasingly sympathetic to the sensitive boy’s fate: to either die in battle or be rejected by his family. The whole group spend a weekend at his ancestral estate to ponder his future. The place is said to be haunted by his soldierly ancestors, especially one rogue who killed his wife and son in a rage, and this fellow’s portrait has a particularly powerful effect on Owen. Between his sadistic fiancée and his merciless relatives, it seems he has no resort other than to retreat. But the irony is that he has the most soldiery character of any of his ancestors – he goes forward. He reject his family’s expectations and sleeps in the haunted room where he plans to do battle with his family ghosts and meet his fate like a soldier. A tragic parable of callous militarism that has often been said to predict the thoughtless loss of an entire generation in World War One.

Like “The Ghostly Rental,” “Owen Wingrave” owes much to the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe, and like “Rental,” “Wingrave” is particularly in debt to “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Poe’s story related the history of a house which was supernaturally grafted into the bloodline of its resident family. The Wingrave house seems to have a personality, character, and even spirit of its own, one indivisibly sutured into the collective family soul. The house stands as a symbol and totem for the Wingraves, and its brooding gloom is a sign of danger for the rebellious Owen. Both stories concern the powerful, rapaciously violent influence that history can have on an individual. The sheer momentum of centuries’ worth of slaughter, death, and combat is enough to drag Owen into the riptide of his family’s history, where he is overwhelmed and smothered in spite of his ideals. James’ story attracted a high amount of criticism from contemporary liberals like George Bernard Shaw who felt that Owen’s demise was disappointing; they wanted the nonconformist to survive and thrive. Shaw seethed to James in a letter about the story: “You have given victory to death and [old-fashioned values]: I want you to give it to life and regeneration.” James tersely replied that had Owen survived, the readership would have immediately been aware of the plot flaw: Owen must die – there is no other way. James infuses the tale with such a high degree of doom and fate – it is almost savage the way that Owen is so unquestionably destined for destruction. James deftly blends progressive values and a cynical, innately conservative worldview into “Owen Wingrave,” leading to an emotionally complex, philosophically nuanced, timeless parable of national sin and the sacrifice of youth for the sustenance of the corrupt state.

Timeless, indeed – Britten’s opera has been set during World War II, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and the Wars on Terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq. Clearly it has been a story that transcends Victorian Britain – one which can be applied to the days of the Spartans, the Romans, the American Civil War, the Napoleonic Wars, the Wars of Religion, gang violence, Latin American coups, the Israeli-Palestinean conflict, and more. This is a narrative that speaks directly to the maxim: “older men declare war. But it is the youth that must fight and die.” Mary Roberts Rinehart said it even more viciously: “I hate those men who would send into war youth to fight and die for them; the pride and cowardice of those men, making their wars that boys must die.” “Owen Wingrave” certainly appears to be a philosophical prototype for All Quiet on the Western Front, with its themes of wasted youth, corrupted innocence, misunderstood virtues, and discarded promise. But “Wingrave” is far more unsettling when the very real machinery of Owen’s assassination become apparent – the virtually undeniable collusion of his hateful grandfather, spiteful aunt, and resentful lover with the brutal spirits of the Wingrave home. Like Poe’s Usher, Wingrave is destroyed for breaking rank with his family destiny (in Poe’s story it was for attempting to bury his twin sister alive – thereby breaking the family bond), and found prostrate on the floor – executed for treason. Despite Shaw’s complaints, however, Owen’s death is not so much an execution (unlike Usher’s undeniable slaughter at the hands of his vengeful sister), as it is a warrior’s death. He falls on the supernatural battlefield like a brave soldier, ironically meeting his family’s expectations by virtue of his nonconformity and rebellion. He has assured us of his manhood. And manhood is a monomaniacal obsession in this story, one only enhanced by the homoerotic substructure of Coyle (who seems to be developing a deep crush on Owen – one that leaves his terrified wife shivering alone in her bed while he watches over his charge).

Manhood – particularly as defined by the vicious Kate (whom Coyle un-feminizes by calling a “brute” – a name typically applied to domestic abusers and males who mistreat women) – is deeply grafted into the concept of gentlemanliness. The word “gentleman” did not mean “a polite, respectable man or manners,” but rather a person of good birth, breeding, and prospects. It is a caste that is defined partly by socio-economic status, partly but pedigree, and partly by character. To not be a gentleman is not to be rude, it is to be less-than – an emasculated, lobotomized knave who is not spiritually, psychologically, socially, or morally adequate. The Wingrave family (and Kate) define masculinity by courage as opposed to cowardliness. The courageous are admired (their portraits are featured on their walls even when they are murderers), and the cowards are unmanned and cut off. The girlish, simple-minded Lechmere is terrified to even suggest that Owen may be a coward because of the emasculating implications, and Kate savagely attacks Owen’s masculinity by daring him to sleep in a chamber which she (arguably) knows will be the site of his destruction. But Owen surprises us all when he announces that not only will he sleep in the room, but that he already has. Owen – as Coyle suspects – has the best, most mature character of anyone in his family. He has gone to the battlefield where he knows his demolition will take place. He is willing to confront his giants – the wrathful spirits of his violent descendants – and he returns each night to the field of battle waiting for his adversaries to arrive. And the do. And they vanquish him. But I think Shaw is wrong: Owen dies, but death does not triumph; his character triumphs. He sacrifices himself – a Christ-figure who willing arrives at the Garden of Gethsemane – and proves his mettle in a staggering way. “Owen Wingrave” is perhaps James’ most layered ghost story, and much more could be written about it, but it ultimately boils down to one troubling thought that haunted James as he read about Napoleon’s glorified campaigns beside a handsome young man with poetic tastes and a sad eye: what is lost when we urge our youth to follow the patterns of the past? What is wasted when we assume that their character is the less because it is younger? Are we justified in perpetuating centuries’ old models in the name of tradition, or are we preventing something rare and beautiful from blooming by smothering it in our vicarious aspirations?